Cultivating Resistance: An Analysis of Exhibitions of Åsa Sonjasdotter’s Art in the Context of the Plantationocene

This article explores the history of crop variety purification and its role in the rise of monoculture. The Swedish artist Åsa Sonjasdotter examines the development of genetics, which evolved alongside the rise of National Socialism. The regime of purification sought to find ‘pure’ plant varieties following the New Testament imperative to ‘separate the wheat from the chaff.’ The article traces the creation of ‘ideal plant bodies’ (J. van der Ploeg) and their contribution to the spread of monocultures in the Plantationocene (A. L. Tsing, D. Haraway). Through an analysis of Sonjasdotter’s art exhibitions, the author highlights subversive practices that challenge the dominance of monoculture, a system that benefits a narrow group of stakeholders while harming the environment.

Keywords: biopolitics; agriculture; Plantationocene; Åsa Sonjasdotter

The Earth eventually began to revolt, but it was a silent, slow revolt that humans did not heed, for there was yet more virgin land to conquer. Because they had become divorced from the land, humans could not understand the symptoms and did not see the correlation between cause and effect. They despised the Earth as much as they impressed themselves with their own power in the belief that they could turn nature into a blind and willing slave to their every command. In Sweden, we are not entirely unaware of the hardships other nations suffer as a result of the protesting Earth. We are, however, exceptionally reluctant to recognise the symptoms when they appear at home.

Elisabeth Tamm, Elin Wägner

The above motto comes from Peace with the Earth, a 1940 manifesto penned by two Swedish suffragettes, Elisabeth Tamm and Elin Wägner. Tamm was a committed politician, one of the first Swedish parliamentarians championing women’s rights. She was also involved in farming, echoes of which can be found in Peace with the Earth. Wägner was a writer and activist for the natural environment, peace and women’s rights, and a member of the Swedish Academy. The fervent tone of Tamm’s and Wägner’s pamphlet, which runs to more than eighty pages, speaks to how relevant its topics were at the time. The issues in question include the future of agriculture, ecologic awareness and an awareness of the human relationship with the land/earth understood primarily as a metaphorical framework including coexistence with telluric and organic matter rather than as relations of ownership (Archive Journal, 2020, no. 9, p. 8).1 Tamm’s and Wägner’s manifesto serves as the leitmotif of the work of Åsa Sonjasdotter, a Swedish artist who explores relations between plants and humans in the context of different ways of growing plants. I use the word leitmotif in its literal sense too, for its echoes – in keeping with the iteration principle – recur throughout Sonjasdotter’s oeuvre.

I first came across Sonjasdotter’s work at the 2019 Warsaw Biennale, where I saw ‘Floraphilia: The Plant Revolution,’ one of the first exhibitions in Poland entirely dedicated to plants conceived as social actors. As the organisers emphasized, the show sought to mark a break from the reactionary perception of plants as motifs or interior design elements, bringing out their ‘emancipatory and agential potential.’ The work on view included Sonjasdotter’s art project whose title, ‘The Order of Potatoes,’ was a direct reference to Foucault’s biopolitical discourse, addressing the primary issue of potato cultivation. ‘The Order of Potatoes’ tracked the story of how the cultivated varieties of potatoes had been purified, because, as the artist pointed out, the food industry modifies crops to sustain the existence of a handful of the most productive varieties, dismissing others as ‘too hybrid’ and not including them in wide distribution (ibid.). This strict selection in line with the categories of ‘desirable’ and ‘undesirable’ is an act of industrialized management, which serves to capitalise on the knowledge of the adaptability of plants that farmers have grown and harvested for centuries.

In other words, Sonjasdotter’s project focused primarily on the New Testament imperative of separating ‘the wheat from the chaff’ in the context of specific crop varieties in the age of industrial agriculture. In doing so, it revealed the more-than-human biopolitical management of crops, which enabled the development of monoculture crops, thus leading to a decline in biodiversity. This kind of management resonates well with a diagnosis formulated by Foucault, who saw biopolitics as ‘a matter of organizing circulation, eliminating its dangerous elements, making a division between good and bad circulation, and maximizing the good circulation by diminishing the bad’ (2007, p. 32). Foucault did not address the subject of plant biopolitics, but his diagnosis of the mechanism of division into good and bad and the elimination of dangerous elements threatening the status quo provided direct inspiration for the project of Sonjasdotter, who made more-than-human biopolitics in the context of cultivated plants central to her work.

As only a part of the Swedish artist’s project was included in the Warsaw exhibition, I went to Karlsruhe’s Badischer Kunstverein to see Sonjasdotter’s first retrospective, ‘The Kale Bed Is So Called Because There Is Always Kale in It,’ which inspired me to reflect on the biopolitical management of crop bodies in an era Anna Tsing and Donna Haraway termed the Plantationocene. This short piece will seek to, firstly, bring order to the work included in the show and, secondly, to contextualize it through subject literature.

Human–plant geographies2

Curated by Anja Casser, the Badischer Kunstverien exhibition was a comprehensive selection of Sonjasdotter’s work, divided into five sections. There is always a potential danger in this kind of ‘comprehensive’ selections as they tend to be too cursory and selective. A problematic thing about the Karlsruhe exhibition was that most of the projects on view had been created as part of artist residencies (in Ireland, Sweden or Germany) and combined with site-specific activities. Thus, lifting each project out of its local context and into traditional white cube spaces denied visitors the full experience of it. The first part of the exhibition, ‘The Kale Bed Is So Called Because There Is Always Kale in It’ (which was also the title of the whole exhibition), featured a project the artist created in 2017–2023 in Ireland in collaboration with the photographer and artist Mercè Torres Ràfol. The centrepiece of this section was a collection of collages depicting black and white archive photographs of kale cultivation in Ireland, with clippings of contemporary photographs of kale pasted over them. A few specimens of dried kale were placed on these compositions, printed on two huge pieces of fabric. Apart from this striking display (the swaths of fabric were several metres long), however, visitors were offered little in the way of information on the project that had inspired the exhibition. The curatorial descriptions were rather succinct and provided only basic information such as explanations of what was on display.

A copy of Archive Journal left at the entrance to the show served as an introduction to the project. The publication, printed in the form of a collection of newspaper pieces (with their typical tone fusing sensation and information), was produced in collaboration with Project Arts Centre, Dublin, as a companion piece to an exhibition mounted in Ireland in 2020. It stated that elements of the art installation referenced the practice of storing seeds of kale and other plants in the farmers’ clothes worn at harvest time. One might say that the copy of Archive Journal fulfilled the ‘archive’ promise of the exhibition title, offering information on its historical context.

Kale had been widely grown in Ireland until the 17th century before the country’s agricultural economy began to rely on the cultivation of potatoes. Sonjasdotter accessed the archives of the National Folklore Collection, where she found notes on kale cultivation and photographs of kale growing close to farm buildings known in England and Ireland as byre-dwellings. She also gathered documentation on the process of collecting wild varieties of kale by peasant farmers. According to the artist, kale and other species of plants of the cabbage genus, such as mustard (Sinapis L.), played a prominent role during the Great Famine in Ireland (Feehan, 2003, p. 161). The famine began in 1845 when the bulk of the potato crop was destroyed by a fungus-like microorganism, a water mould called Phytophthora infestans. The famine predominantly affected the poor classes, who depended heavily on the potato crop. Cereals were also widely grown in Ireland at the time but largely by wealthier landowners, who exported them to Britain (Curtis, 2002, p. 227). It was then that the various varieties of kale, which were spreading in Ireland’s coastal areas, became a food staple. Sonjasdotter found photographs showing the harvest of the sea kale, a halophyte from the cabbage family, growing on the sandy beaches and dunes of the Irish coast, which was harvested during the Great Famine. By showcasing this material, the artist traces the forgotten history of plants that were of little interest for agriculture but played a significant role during the famine, which ravaged Ireland between 1845 and 1849. In a report Sonjasdotter found, the plant researcher R.M. Murphy notes that Ireland has a long tradition of collecting and storing seeds of plants of the cabbage genus. Between 1982 and 1984, the researcher was involved in an international study of seeds from Irish farms. As he writes in his report, forty per cent of farmers had given up collecting the seeds of local plant varieties by the 1980s due to the spread of industrial cultivation and the introduction of official lists of licensed seeds and modern plant hybrids in order to ensure better yields (Murphy, 1984). Although the story told by Sonjasdotter has no explicit conclusion, it suggests that she blames industrial food production for the genetic erosion of many species – I return to this question further on in my examination of other sections of the exhibition.

Cultivating Resistance against Monoculture

One of the most enlightening sections of the show, ‘Cultivating Abundance,’ centred on forms of resistance to monoculture farming and on the industrial monopolization of agribusiness and it included a video Sonjasdotter made in 2022 in dialogue with the Alkorn Association and the plant breeder and researcher Hans Larsson. The documentary outlines the monoculture technology, which started to be developed at the Swedish Seed Association in the 1880s, as researchers associated with the organization searched for the ideal plant, the ‘pure’ and highest-yield variety of each species.

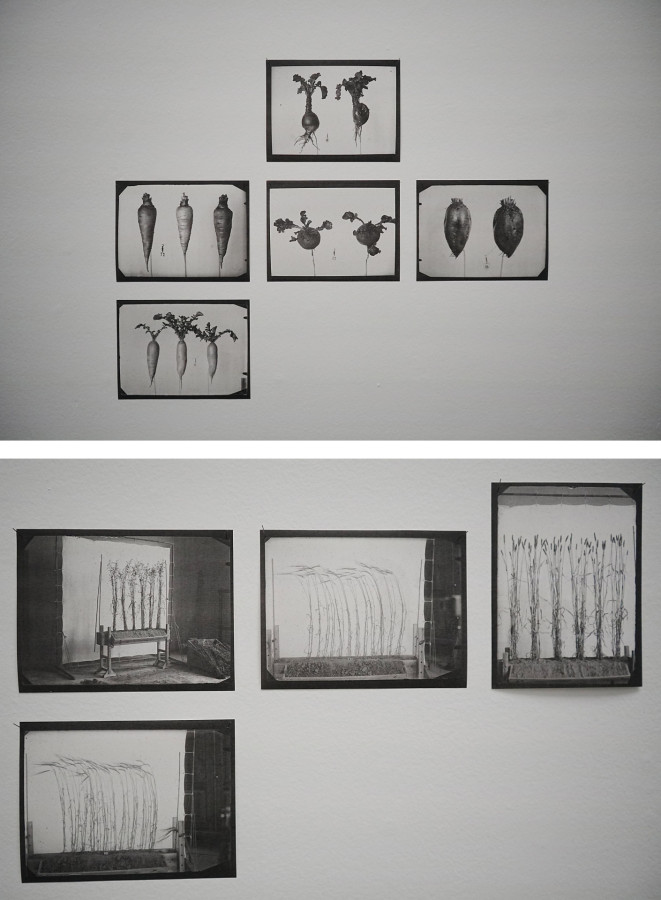

In the first part of the video, which served as an archival introduction to the story of modern plant growing techniques, a voiceover discussed the importance of gelatine silver prints from the collection of the Swedish Seed Association in Svalöv. These black-and-white photographic positives, which consisted of silver bromide suspended in a layer of gelatine, documented the efforts of scientists in their quest for the ‘ideal type of crop’ – the prints showed beet and potato tubers side by side and upright ears of cereal, which scientists sought to standardize as much as possible in order to arrive at an identical shape and texture, documenting their results in photographs where each cultivar was measured and compared with the others.

Photos from the author’s private archive, taken during the exhibition The Kale Bed is so Called Because there is Always Kale in it in Badischer Kunstverein in Karlsruhe.

At Svalöv, scientists applied a standardizing method described as a ‘complete reversal of the old understanding of breeding.’ Instead of collecting and storing selected seeds, a practice that had also served, since ancient times, as a kind of archive of plant adaptation processes in different conditions and latitudes, they worked to ‘identify and control uniformity’ in the existing seeds. The concept of the ideal plant required many years of controlled cultivation over several generations, which yielded ‘pure lines’ from which genetic ‘impurities’ had been expunged (Sveriges Utsädesförening 1886–1936, 1936, p. 168). In the process, plants that exhibited interesting traits, and hence aspired to be perfect, were transferred from fields to laboratories where cultivated varieties were crossed with other pure lines to produce the perfect cultivar. The resulting cultivar was multiplied en masse, distributed and legislatively legitimized, thus gaining a monopoly position on the seed market.

The results of the quest for ideal and pure biological plant types were soon translated into a search for perfect human bodies. 1922 saw the opening in Uppsala of the Swedish State Institute of Racial Biology (SIRB), which followed in the footsteps of the genetic work done at Svalöv. Shortly afterwards, in 1927, the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für Anthropologie, Menschliche Erblehre und Eugenik was opened in Berlin, followed, in 1928, by the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für Züchtungsforschung in Müncheberg, both modelled on Swedish centres (Björkman and Widalm, 2010, p. 379–400).

Sonjasdotter found a private photo album of a former employee of the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für Züchtungsforschung, containing reprinted photographs made at Svalöv, a testament to the fact that the ideas adopted in Germany had arrived from Sweden. The source of the practice of ‘racial and species purity’ used to be traced to the ideology of the Third Reich, but similar practices had been pursued earlier, in the early twentieth century, in the field of plant cultivation in Scandinavia.3

The genetic pursuit of hygiene in plant bodies would later contribute to the launch of political projects involving the execution of humans (Saraiva, 2016). As noted above, the first part of the video documented the process of crop uniformization. In the next part of the exhibition, ‘The Documentation of Research,’ viewers could see up close prints of the gelatine silver photographs (which were also included in the video in time-lapse clips) and examine scans of documents found by the artist.

(Bio)diversity of adaptation processes

The next part of the video is themed around the researcher and plant breeder Hans Larsson, who in the early 1990s initiated a project on organic forms of farming at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences in Alnarp. Housed in a building on the university campus is a seed bank operated by the Nordic Genetic Resource Centre, holding seeds of many local plants grown by Swedish farmers. In contravention of the rules of the seed bank, Larsson and other project participants used some of the bank’s seeds to grow plants in the campus in order to observe their properties ‘in practice.’ He then went a step further and started experimenting with the seeds across Sweden to test their adaptability under varying conditions. This move, Sonjasdotter explains, was an act of resistance against the locking away of all local varieties, which had been grown by smallholder farmers for centuries, and replacing them with ones widely distributed for monoculture cultivation. The significance of the title of this section of the show, ‘Cultivating Abundance,’ is revealed here – Larsson’s activities were an act of resistance against the industrialization and monoculturation of the landscape, first by testing and restoring the vitality of forgotten varieties, then by handing them over to small-scale Swedish farmers for cultivating abundance and biodiversity. Larsson drew on the tradition of farmers passing on seeds of different varieties to other farmers, which was cut short by the advent of the industrial production of ‘pure’ varieties. Later, Larsson moved on to work with a group of individuals with whom he founded the Allkorn Association to extend the ‘test cultivation’ of seeds to other climatic zones. In the video, Larsson points out that this practice has brought many varieties, including flat wheat and rye from Fulltofta, back into the fields.

Speaking about his practice, the researcher addressed issues fundamental to the ecological paradigm underscoring coexistence with the environment in opposition to instrumental approaches to land resources and yield maximization: ‘In order to breed plants, you need to find locations that target the climate and the environment. Everything about the surroundings is important: the trees, the water sources and the wild plants as well. You are, in fact, co-creating an environmental space.’4 Monoculture farming is predicated on the opposite idea: that of finding ‘ideal bodies’ offering the highest possible yields once the soil has been adapted. As a result, as Larsson points out, monocultures become more susceptible to diseases, which can rapidly cripple whole crops. Along similar lines, Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing and Donna Haraway proposed a new configuration for the concept of the Anthropocene. By introducing the semantic category of the Plantationocene, the researchers pointed to the coupling of the monoculture model with agribusiness and with the colonial vestiges of land ownership and wage labour. At the same time, Tsing and Haraway highlighted the ecological issues addressed by Larsson, that is, the rapid transformations of pests and pathogens that are ‘experimenting’ with the abundance of food available on plantations, coming up with new ways of appropriating and attacking monocultures:

Second, plantations allow sometimes quite rapid transformations of pests and pathogens that create forms of virulence that didn’t exist before. The pathogens are experimenting with ways to make use of the bounty of food in the plantation. At the same time, plantations are linked in global commerce. They are often sending the same materials back and forth across the globe, allowing hybridization across closely related but geographically separated pathogen species. These hybridizations produce pathogens that can attack new hosts and in innovative ways. So we see a proliferation of newly virulent pathogens that is really unheard of in the world as far as I can see. They do not stay on the plantation. They make other kinds of agriculture, such as small-holder peasant cultivation, much more difficult than they were before (Haraway and Tsing, 2019).

As a result, we are increasingly seeing newly emerged pathogens, and they are moving beyond plantations to other types of crops, including those grown on smallholder farms. It is clear that while the objections of people like Larsson concern the huge food industry at the micro level, they also encompass, at the macro level, the broader ecological paradigm of caring for the wellbeing of all crops and the preservation of biodiversity. I have invoked the conversation of the American researchers for a kind of counterpoint and afterthought, as both Sonjasdotter and Larsson describe the challenges faced by small farms due to the existence of industrial scale cultivation, but they also address the ecological effects of monocultures in an era that Tsing and Haraway call the Plantationocene. The findings of Tsing’s research, which she presents in a landmark book for the environmental humanities, The Mushroom at the End of the World, resonate well with Sonjasdotter’s research and artistic work. In her book, Tsing describes the process of standardizing monoculture crops, which are full of ‘ideal plant types,’ referencing the research of Jan van der Ploeg (Tsing, 2015). In the 1990s Jan van der Ploeg defined two crop models, ‘art of the locality’ and ‘scientific knowledge,’ which profile the path of proceeding with crops, revealing the underlying paradigms. For Ploeg, scientific knowledge in this context consists of employing biopolitical practices of partitioning crops into desirable and undesirable species (Ploeg, 1993, p. 209–27). The ‘art of the locality,’ by contrast, represents a different relationship to the land/earth, one arising from care, which at the same time fosters heterogeneity of varieties by maintaining multiple genotypes across space and time (ibid.). This type of coexistence with the land mostly involves the tuning of plant varieties to the soil and local conditions. The opposite of this approach, monoculture, is designed for the needs of ideal types of altered plant bodies. In this case, it is the soil that is adapted to the ‘improved’ plant species with the aim of producing the highest possible yields in the shortest possible time.

Sonjasdotter’s investigations that involve the tracing of archival content documenting the process of monoculture development are central to the artist’s oeuvre. On the one hand, like van der Ploeg, Sonjasdotter presents the foundation of the emergence of monoculture cultivation seen as the management of plant bodies with a view of ensuring they meet the criteria of ideal quality and productivity, focusing on what Timothy Morton calls the quantitative criterion. On the other hand, the Swedish artist does not leave us with a synthetic diagnosis concerning what Morton refers to as agrologistics, that is, the premise whose nodal point prioritizes scale over crop quality. At the same time, Sonjasdotter seeks other ways of coexisting with the environment, which would correspond to the words of Hans Larsson, who claims in Cultivating Abundance that cultivation is primarily about being sensitive to the surrounding assemblage of different actors.5 In her artistic intervention, Sonjadotter not only brings stories unearthed from archives into a museum space but also explores alternative ways of cultivation, which van der Ploeg would subsume under ‘the art of locality.’ One such alternative way is Larsson’s practice of growing different species at different latitudes to see how the seeds perform in different (including extreme) conditions. This kind of knowledge seems particularly relevant as we face looming ecological crises that make the future even more unpredictable.6

Ecological knowledges

The Karlsruhe exhibition shed light on the turn that followed the invention of modern and industrial plant breeding, which was accompanied by the disavowal of traditional farming methods. Sonjasdotter not only collects archival content, such as copies of photographs or diary scans but above all follows the path of ecological knowledge, deliberately ignored by the contemporary mainstream industry, which designs and business-narrativizes its practices to generate surpluses and profit. She traces the forgotten stories of entanglements between people and plants that have been marginalized in the general perception of agribusiness development, such as the harvesting of the sea kale during the Great Famine in Ireland or the cultivation of local varieties by a group of farmers from the Larsson-conceived Allkorn Association.7 The artist advocates a return to the traditional practice of seed sharing and the cultivation of different plant varieties, resisting the imperative of using nothing but the unified sources distributed by large corporations.

As noted above, the Karlsruhe exhibition provided only a fragmentary view of the artist’s oeuvre as it had to be condensed into an overview held at one venue. A venture like this is bound to be fragmentary and only superficially comprehensive. Another problematic aspect was the somehow chaotic narrative arc defined by the selected works: starting in 19th-century Ireland, it moved on to 21st-century Sweden before returning to an archive of documents charting the rise of fascism and showcasing reprints of a Swedish suffragette manifesto written during the Second World War – each of these elements conceived as a different project, a self-contained entity.

It was only later, when I began to piece together my memories of the exhibition, that I realized that what united all the projects, documents and inspirations was their opposition to the top-down directives imposed by a growing industry, which were slowly leading to the implementation of biodiversity-free crops. The organizers wanted the exhibition of Sonjasdotter’s work to be a manifestation of the practice of subversion against this form of domination, which, though highly profitable for a narrow group of stakeholders, has an adverse impact on the land/earth.

The Swedish suffragettes wrote an impassioned manifesto in the name of ‘peace with the earth’ at a time when agribusiness had already spread across Europe. Sonjasdotter offers a behind-the-scenes look at the creation of this regime of purification, pointing to her native country as the source of the German industry’s inspiration. The artist depicts two different paradigms: the industrial and the local (or organic), which coexisted in Sweden. This duality continues to this day, as demonstrated by expanding companies and lists of seeds awarded EU certificates. On the other side are groups of seed bank users such as Hans Larsson. While Sonjasdotter reveals to visitors the roots of genetics, a discipline that developed in parallel with National Socialism, she does not elaborate on the closely related topic of the production of pesticides sustaining contemporary monocultures. As Frank A. von Hippel, Professor of Biological Sciences at Northern Arizona University, points out, ‘pesticides also are integral to the history of modern warfare and environmental destruction.’ Like Sonjasdotter, he begins his book The Chemical Age: How Chemists Fought Famine and Disease, Killed Millions, and Changed our Relationship with the Earth with the history of the potato in Europe and the Great Famine in Ireland: ‘a logical place to begin a history of pesticides is with a chronicle of the potato and the famine it brought to Ireland’ (von Hippel, 2020, p. 9). The researcher notes that the story of the Irish famine represents one of Europe’s first and most poignant effects of globalization and the introduction of monoculture, one that proved lethal for millions of people.

What I think was missing from the Badischer Kunstverien exhibition was something that would seamlessly combine all the stories scattered across locations and linked to Sonjasdotter’s artist residencies. The artist makes visitors realize the existence of two parallel narratives: one calling for coexistence with the land and for organic cultivation and one underpinned by scientific knowledge, which seeks purification and rapid intensification of crop growing, combining discovery with agribusiness. The existence of an ecological paradigm in the first half of the twentieth century is brought into further relief by what Christophe Bonneuil and Jean-Baptiste Fressoz wrote in the context of the Anthropocene, pointing out a long-standing awareness of ongoing environmental degradation:

Far from a narrative of blindness followed by awakening, we thus have a history of the marginalization of knowledge and alerts, a story of ‘modern disinhibition’ that should be heeded. Our planet’s entry into the Anthropocene did not follow a frenetic modernism ignorant of the environment but, on the contrary, decades of reflection and concern as to the human degradation of our Earth. Likewise, the Great Acceleration of the Anthropocene after 1945 in no way went unperceived by the scientists or thinkers of the time (Bonneuil and Fressoz, 2015, p. 76).

The Great Acceleration certainly did not go unnoticed by female thinkers and activists in the first half of the twentieth century. In 1940 two of them wrote the manifesto Peace with the Earth, which I discuss and quote from at the beginning of this article and which inspired Åsa Sonjasdotter to explore the inglorious past and point to the possibility of choosing a better path towards a more sustainable and ecological future.

Translated by Joanna Przasnyska-Błachnio

Niniejsza publikacja została sfinansowana ze środków Wydziału Polonistyki w ramach Programu Strategicznego Inicjatywa Doskonałości w Uniwersytecie Jagiellońskim.

This publication was financed by the Faculty of Polish Studies as part of Strategic Programme Excellence Initiative at Jagiellonian University.

A Polish-language version of the article was originally published in Didaskalia: Gazeta Teatralna 2025, No. 185, DOI: 10.34762/5xtk-7d34.