Riots in Performing Arts Research: a Close-up of Dance, Movement and Choreography

Abstract

The article addresses the issue of badania artystyczne (BA; literal translation: artistic research) in the field of performing arts, with a particular emphasis on movement, dance, and choreographic practices, and set in the Polish context. The authors aim to identify and describe examples of artistic research processes in the field defined above; to explore the specificity of BA practices and the contexts in which they are realized; to share tools, methods, and knowledge about them at the level of the BA practices themselves and of studies on BA. The paper is divided into five parts: 1) a definition of artistic research; 2) an auto-choreo-ethnographic reflection; 3) a spider-map of BA practices; 4) an in-depth analysis of three artistic research processes (I: Przyszłość Materii (The Future of Matter) by Magdalena Ptasznik; II: Badanie/Produkcja (Research/Production) curated by Maria Stokłosa; III: a continuum of practices by Ania Nowak); 5) ‘interlacing’ – a cross-sectional reflection. The structure of the narrative is based on two orders: a) a textual order – the main axis of the article; b) a graphics-mapping order – a complementary collection of visual-textual materials presented on the Research Catalogue platform.

Keywords: badania artystyczne; artistic research; performing arts; methodology; dance; case study

Introduction

The article deals with badania artystyczne (BA; literal translation: artistic research) in the field of performing arts, with particular emphasis on movement, dance and choreographic practices and set in the Polish context. The aims of the text include three vectors. The first is noticing and recording: identifying, signalling and describing examples of the artistic research processes within a defined field. The second is exploring and analysing: exploring the specifics of BA practices and the contexts in which they are implemented. Here we focus on noticing dependencies and on interpreting and considering the trajectory of their development. The third vector is focused on sharing tools and methods and the knowledge that flows from them: knowledge on the exchange of sources, concepts or conclusions primarily at the level of BA practices themselves, but also of studies on them. Therefore, on the one hand, in the examples we analyse, we pay special attention to the exchange of content and artistic research experiences, including those in progress. On the other hand, we want the process of creating this text to be transparent, which is why we have included the auto-ethnographic thread in the narrative and provided access to our research notes.

We have divided the text into five parts: a definition of artistic research; an auto-choreo-ethnographic reflection; a spiderweb-map of BA practices; an in-depth analysis of three research and artistic processes (The Future of Matter by Magdalena Ptasznik; Research/Production curated by Maria Stokłosa; Ania Nowak’s continuum of practices); ‘Interlacing’ – a cross-sectional reflection. We used two narrative orders. The first, the text, is the main axis of the article. The second, graphics-mapping, is a complementary collection of visual-textual materials presented on the Research Catalogue platform, excerpts from which we present here as illustrations.

The auto-choreo-ethnographic perspective: process, working methods, cognitive dispositions and shifts

Before we go on to explain how we perceive the essence of artistic research, we would like to clarify our perspective and outline the dynamics of our analytical work. In the course of cooperation on this article, which we were invited to write by the Pracownia Kuratorska1 (Curatorial Workgroup), we noticed a displacement of our own research attitudes and points of view, which in the context of the description of movement practices seemed to us attractive from a cognitive perspective and worth sharing with our readers. We began our research on BA in the field of the visual arts we know, and, by approaching practices at the fringes of performative work with movement and body – less frequented by us – we observed the insufficient compatibility of our earlier assumptions. A critical look at the mismatch added to the study of the encountered cases by allowing us better to cater to their specificity. By describing our own movements in an unfamiliar field, we became auto-choreo-ethnographers2 of our own research processes, and the traces of these movements are indicated here with distinctions.

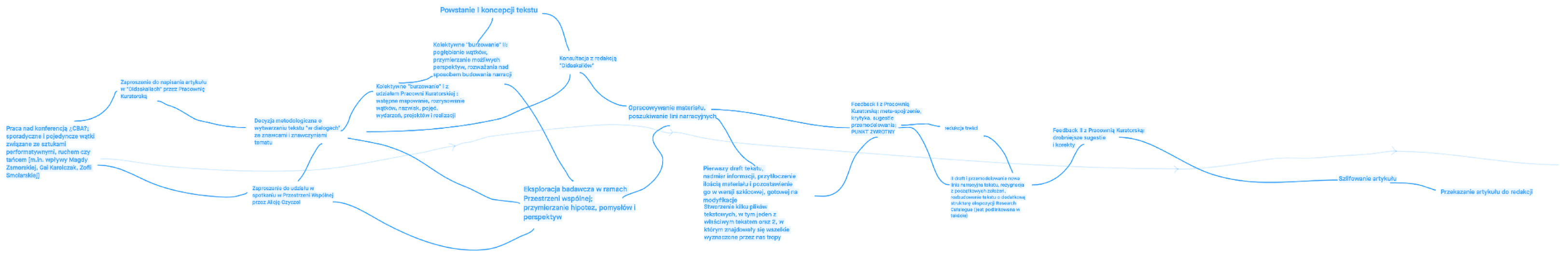

We believe that exploring and systematizing creative research requires close cooperation with practitioners3. For this reason, at various stages of the work on this article, we invited people related not only to BA, but also to movement in its broader context of dance and performance, drawing on the hospitality of people from the Przestrzeń Wspólna (Common Space)4. The semi-formal nature of the sources of our knowledge (which included conversations, consultations and collectively authored notes) turned out to be difficult to classify as a classic textual narrative supplemented with quotations in footnotes. In order to provide behind-the-scenes insights into the research process, we documented the subjective chronology of events visually.

https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/1228805/1228806

We ran into a variety of tensions, realizations and strategies in acquiring the knowledge needed for this article. The first one concerns our research dispositions: although we identify with the field of art in the broader sense, embedded in the discourses of visual arts, humanities and social sciences, we employ different vocabularies and knowledge exchange models from those characteristic of performance practices. So we started out with a sense of competence anxiety5 that our cognitive devices were incompatible with the practices and rules of movement/dance/choreography (M/D/CH) and that our knowledge was insufficient. Therefore, we asked the Pracownia Kuratorska, Przestrzeń Wspólna6 and the editorial office of Didaskalia. Gazeta Teatralna (see illustration) to guide us through this unfamiliar territory and to brainstorm research ideas. In the process of harmonizing pre-designed structures to the information obtained, we got tangled up in the trap of perfectionism, related to an imposter syndrome.

We became entangled in the excessive descriptive order and accuracy in this newly accessed world and found ourselves supported by critical remarks of the Pracownia Kuratorska. It was with its members that we systematically confronted our imagination and consulted on conducting our analysis and developing content. As a result of this cooperation, we focused on describing a few examples that became clear in our perception, and resigned from drawing up the full panorama of movement phenomena, let alone cataloguing it. Looking at the feedback technique typical of performing arts, we decided to ‘steal’ it and weave it into our own methodology. Only the departure from the classic figure of lone female researchers and the use of a method not native to the writing of academic texts made it possible to develop an adequate form of narration7.

1. What is artistic research and what characterizes it?

Not wanting to multiply the definitions, we decided to paraphrase the explication that we developed for the BA lexicon published in ‘Notes Na 6 Tygodni’ (Brelińska, Małkowicz-Daszkowska, Reznik, 2021, p. 93). We started work on the definition with a search for the Polish roots of artistic research in the field of visual arts. Then, we initiated a process of disseminating the concept of ‘artistic research’ in Polish academic and artistic circles8 by following how it resonated in this environment. We treat the BA concept as an internally diverse landscape and therefore try to define it in a way that leaves it as open as possible to be applied to dance and movement and to being updated based on investigations flowing in from new areas.

Artistic research is an area of heterogeneous practices situated between science and art as well as other areas of social activity, and its purpose is the production and exchange of knowledge. These practices are the result of connecting – in any combination – social sciences, humanities, the exact and natural sciences, visual and performing arts, music, design, architecture, curatorial practices, socially engaged activities, and even business. A single BA project contains individual proportions of ‘admixtures’ of knowledge, methods, tools, languages, aesthetics and attitudes that are also derived from areas, fields or niches outside those elicited above: there is no definitive recipe for artistic research. Artistic research focuses on practice, organizing its content, and presents the conclusions and results of this creative investigation in a variety of formats9. It easily inhabits the fertile fringe areas, but it can also arouse various anxieties.

To varying degrees, BA methodologies are realized and often conditioned by their location: the further removed the activities are from institutions, the closer they veer towards methodological frivolity, while in the more structured fields there is a notable tendency to develop theoretical self-reflection. For the purposes of our research, BA draws on the internationally understood term artistic research (AR)10, but we perceive it glocally11 – also in the continuum of experimental traditions of the Polish field of art, including the neo-avant-garde experiments from the 1970s.

How does the above definition relate to homegrown practices arising from movement-based performing arts? Our first intuition indicates that attempts to map local Polish roots may turn out to be more difficult in the performing arts (in particular those related to M/D/CH) than in the visual arts12. What reasons do we sense for this? Several factors can be mentioned, with two being of particular importance:

– the specificity of education within M/D/CH is less ‘academic’ than in other areas of art, focusing on exchanges between individuals, groups, or initiatives and formalized to varying degrees;

– dance/choreography/performance, although an important subject of domestic reflection on practices in the performing arts, ‘is institutionally homeless in Poland’13.

This mainly concerns the necessary infrastructure in the form of production houses, although another manifestation of problems in hosting performances may be dance’s position in the priorities of grant competitions. In both the first and the second case, Polish dance noticeably and actively draws both from foreign experiences and from foreign institutions, as well as from structures in other areas of Polish art (theatre, visual arts). The interlacing developed below is a continuation and development of these threads.

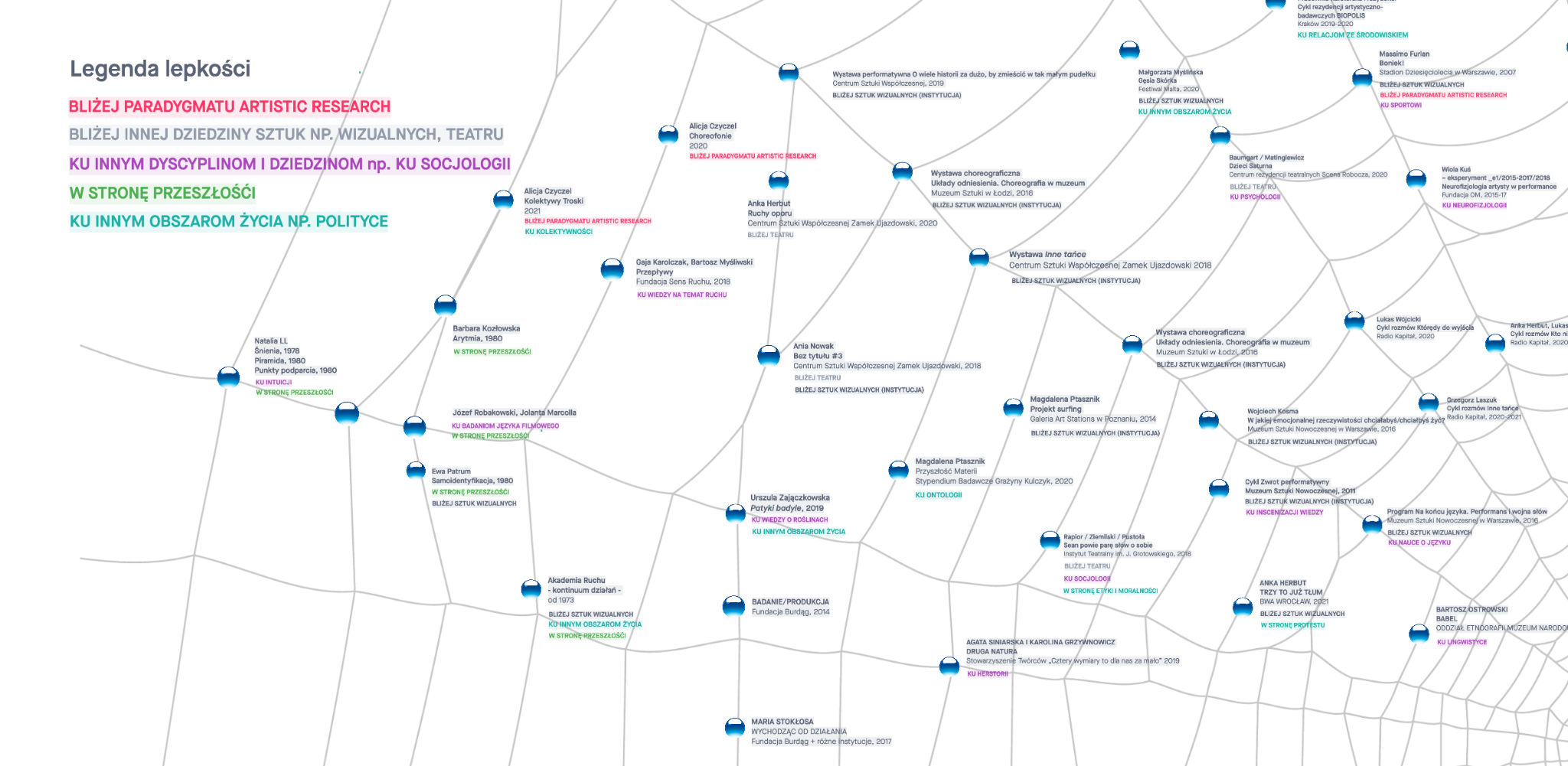

2. Badania artystyczne in dance, movement, and choreography: araneographic activities14

Studying BA practices in the context of movement, dance, and choreography at a time when, newly emancipated, they are only beginning to be formed discursively requires caution. We are driven by a concern to give equal attention not only to mature and well thought-out, meaningful examples, but also to the ‘seeds’ of BA, both in M/D/CH itself and in related areas. When in this context we talk about crossing or renegotiating the existing divisions of art and science, we cannot focus only on the borderline of artistic expression and artistic research. Let us consider the history of avant-garde movements: the creators undertook transgressive activities, oriented not only along the borderline between art and science, but also in other fields of art and in areas of socio-cultural life, e.g. political involvement, everyday life, ecology or technology (Dziamski, 1995; Ludwiński, 2009). For us, this means that we are looking for journeys of concepts, methods, tools, perspectives or aesthetics not only between art and science or their individual disciplines, but also in other areas (Bal, 2012). In the course of our work on this article and collecting materials for analysis, we developed a spider-web map in which we registered selected ‘mature’ examples of BA and their seeds.

https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/1228805/1228806

We provide this to accompany the article as source material that allows for a deeper and systematic insight into research and artistic practices. We also hope that, for readers, it will constitute an independent resource of information threads to be intertwined in their own creative and research processes15. From the entire collection, we have distinguished three cases, which we will examine closely in the next section.

3. Three examples of art research projects rooted in working with movement

When selecting the cases to be analysed, we were guided by several criteria. The most important condition was the availability of sources: texts, recordings, documentation. We also wanted the aforementioned projects to be diversified in terms of the formula and contexts of their creation16. We chose the first case – Przyszłość materii (The Future of Matter) by Magdalena Ptasznik – because it is thoroughly and systematically documented by the author; the process is recorded with clarity and in an easily accessible form. The second – Badanie/Produkcja (Research/Production) – is a recognizable example of BA in the M/D/CH environment, which we referred to while writing this text, and the issues undertaken in this extensive project are related to the self-investigative trait arising from new dance. The third example – the continuum of Ania Nowak’s artistic and research activities on the theme of love – was selected due to its connection with visual arts at the level of both the strategy of sharing results and the institutional background of the production.

In the analysis of the above practices, our interest lies in the following issues: the location and related visibility of the project or the symbolic capital inscribed in it; the subject and its problems; the created formula of cooperation (if any) and the methodology used in the project; the formats of sharing the results; and the effectiveness in achieving the chosen artistic research goals.

Case 1: Magdalena Ptasznik, Przyszłość materii (The Future of Matter), 2020

The Future of Matter project, carried out by the sociologist and choreographer Magdalena Ptasznik17 in 2020 as part of the a.pass18 postgraduate studies programme and the Grażyna Kulczyk research scholarship19, is an example of a transparent BA process. The way it is constructed and formulated may result from the artist and researcher’s experiences abroad. It is about being rooted in the context of the Western paradigm of artistic research, within which there is a canon of institutional requirements and widespread formats of expression. We treat it as one of the many models for conducting BA.

The Future of Matter is a choreographic exploration of the issues of climate change and its accompanying environmental and social crisis. Ptasznik clearly indicates that this project serves to generate knowledge about how choreography can become a platform for critical reflection, strengthening relationships, and creating social change. The fruits of the artist’s creative work include the publication of To discover a fossil on your tibia. Scories and other mutation of scores (Ptasznik, 2021), exploring the possibilities of choreographic notation (score) as a space for generating an exchange between writers and dancers; between thinking and movement, text and body, creating structures and performing within them20. The second component of the publication is the Workshop Manual, containing a set of ready-to-use solutions. Using the manual, Ptasznik shares the developed tools and techniques and, importantly, notes the participation of external authors in their creation and asks for their further attribution.21

From the BA point of view, for projects aimed at sharing generated knowledge, a project’s website is valuable in which the author reveals the entire project structure: she presents research questions and the actions resulting from them; she shares the theoretical background of the project (new materialism, Anthropocene studies, geo-ontology, geo-poetics); she defines its ‘conceptual horizon’ (including ‘ground,’ ‘duration,’ ‘accumulation,’ ‘time that remains’)22; she presents sources and research material (Resources23); she discusses the methodology; she records the course of the project (the Activities24 and Events25 tabs, including residence, research studio Unstable spaces, creating a scenario for workshops, mentoring) as well as its results and accompanying conclusions.

Ptasznik defines this online publication as a ‘dynamic documentation’ of the process, ‘the linguistic and visual record of a choreographic study,’ which corresponds to the free distribution of the resulting knowledge as postulated under the Grażyna Kulczyk scholarship26. In this meta-model of research and artistic work, the dominant features are regularity, meticulousness, going beyond one format or medium of creation and exchange, as well as ‘setting in motion and relationships’. Ptasznik reveals an interesting turning point in the search process, which concerns research self-reflection. It is a ‘self-examination interview’27 in which the artist moves from the research questions with which she started her venture28 to articulating the goal hidden behind them. The implicit intention is to search for the possibility of redefining one’s own practices in the face of the alienating conditions of creating art; resisting the compulsion of productivity29; the production of new tools and spaces for questioning what is being represented; balancing the relationship between one’s own creativity and the research processes behind it.

The artist also admits that this process was an opportunity for her to depart from the research model in favour of a performative result (in line with the neoliberal logic of production by creating, for example, a show or performance) and opening up to creating and sharing reflection as a practice of resistance30. Ptasznik’s self-study, motivated by her own need for emancipation in the field of arts, made it not only possible to deepen her self-awareness but it also contributed to the creation and sharing of tools for BA work. It materialized in the form of a set of exercises and choreographic instructions and stories, which the artist describes by combining ‘scores’ and ‘stories’ to create the neologism ‘scories’. It seems important for us to create, explore and test such procedures (also on ourselves) with the intention of others re-applying them in various contexts.

As part of this project, Ptasznik conducts individual exchanges of a direct nature, e.g. mentoring sessions with Myriam Van Imschoot, Philipine Hoghen, Anna Nowicka, Femke Snelting, Ann Juren and Elke van Campenhout. Ptasznik also supports research within specific stages of the process, e.g. a cooperation with the choreographer and performer Mary Szydłowska; and consults the director and author Aleksandra Jakubczak during her residency at the Centrum w Ruchu (Centre in Motion). The artist also opens her BA process to exchanges at various stages of implementation, including through the presentation of partial results in groups related to the a.pass program, resulting in valuable feedback31. And the book To discover a fossil on your tibia32, designed by Maja Demska, has become a platform for further collaborations – an invitation to co-create an attentive reading community instead of an audience ready to consume the ‘spectacle’33. In the case of this book, engaging in reading means participating in the production of its scattered performance. A small-format, grey-cover publication, it thematically and formally affirms the logic of post-growth and stimulates the embodied observation of one’s own relationships in the human–non-human context. It leads to somatic and psychosocial awareness of the material and non-material environments of which we are a part ([Ptasznik], [n.d.]).

Case 2: Badanie/Produkcja. Taniec w procesie artykulacji (Research/Production. Dance in the Process of Articulation), 2014

During the discussion within the Przestrzeń Wspólna, the participants, when asked about examples of significant research and art projects in Poland, unanimously indicated Research/ Production. Dance in the Process of Articulation, realized in 2014 on the initiative of Maria Stokłosa as part of Fundacja Burdąg (Burdąg Foundation) programme. The project assumed a double residence at the Studio Burdąg (Burdąg Studio), to which were invited practitioners, researchers, and theorists with various creative competences related to movement. The teams consisted of a choreographer and a person writing about dance critically or academically, and the aim was to conduct a joint linguistic narrative and discursive registration of the choreographic process. Zofia Smolarska accompanied the work of Maija Reeta Raumanni and Antti Helminen (Smolarska, 2014), Teresa Fazan and Mateusz Szymanówka described the performance of Renata Piotrowska’s Śmierć. Ćwiczenia i wariacje (Fazan, Szymanówka, 2014), the observers of Surfing by Magdalena Ptasznik and the playwright Eleonora Zdebiak were Agnieszka Kocińska and then Regina Lissowska-Postaremczak (Kocińska, 2014A; Kocińska, 2014B; Lissowska-Postaremczak, 2014), and Maria Stokłosa’s Wylinka was discussed by Anka Herbst (Herbut, 2014). This form of cooperation served to strengthen the relationship between theory and practice (see Zerek, 2016, pp. 132-136). The purpose of the residency was, on the one hand, to define the specificity of the innovative language of movement (see Herbut, 2015) and, on the other, an attempt to create a language of description, venturing beyond the discourse of the time (Zerek, 2016, p. 132)34.

In terms of themes, the cooperations between residents (Piotrowska/Bauer, Fazan/Szymanówki, Ptasznik/Zdebiak, Kocińska, Stokłosy and Herbut) focused on the issues of transformation: death and rebirth, learning about and reinterpreting the world, transgression and examining boundaries, together with accompanying fears and excitement. In our interpretation, they manifest the transformation of the choreographic paradigm and the emergence of a new dance language. Completely different were the issues raised by the Raumanii/Helminen-Smolarska team, which focused on seeking a formula for organizing a community of movement.

Apart from the actions of Raumanii and Helminen, which were realized only at the level of the research process and its documentation, the other projects were presented in the show’s convention under two Warsaw institutions related to the visual arts: Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej (Museum of Modern Art) and Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Zamek Ujazdowski (Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art; Herbut, 2015). These performances, however, were ephemeral shows intended for a small group of people. The texts created in Research/Production, published on dwutygodnik.pl and TaniecPolska.pl, to various degrees enriched with visual documentation, allowed for a more permanent and egalitarian insight into the creative processes and methodologies that constitute them. Here we discuss four different ways of creative writing and the differing natures of the knowledge thus created:

– W poszukiwaniu całości by Smolarska is an ‘observational’ note of the creative process, which reports events from an accompanying perspective;

– Pozycja trupa by Fazan and Szymanówki is a duet of independent observation perspectives, in which, in the narrative, Fazan speaks based on her own experience of the process and direct exchanges with Piotrowska, and Szymanówka leads the description through external reference and institutional-production contexts;

– Generating a narrative based on interviews, which in Pracujemy z ograniczonym chaosem and Przedmioty w akcjachtook the form of dialogues between Kocińska/Ptasznik and Zdebiak. Lissowska-Postaremczak, on the other hand, created a synthetic account of two interviews;

– Kontrolowana dezorientacja. Wylinka, vol. 1: Herbut created an essay of a literary nature, making a poetic translation of the experiences of participating in the process, of being present in the experience.

It is worth noting the clear distinctiveness of the research and creation processes from the meta-reflection arising about them, because it is the co-presence of two components that determines the research and artistic dimension of the project. While it is possible to reconstruct the methods and techniques used in creative processes and their course to varying degrees, the knowledge about how actors and writers cooperate over actions remains rudimentary. One can get the impression that these processes were autonomous, and the texts were mostly created from the position of an observer with an unknown degree of involvement. From this perspective, Research/Production appears to be both a research and artistic project, but split between theory and practice.

Research/Production, for which ‘Production/Research’ would be a more appropriate title, was initiated as a research and artistic harbinger35 on a foundation of Polish dance and choreography, the aim of which was to bring out the language of meta-reflection. As a result, a ‘self-investigative’ project was created that was largely hermetic in terms of communication, being accessible primarily to people closely related to dance. It is worth emphasizing, however, that the nature of these activities was a manifestation of exceeding the condition of ‘solo generation,’ consisting in the transition from self-reflective activities towards activities integrating self-knowledge (theoretical, methodological) with the search for answers to problems rooted in non-dance contexts and its exchange with other environments. The use of this knowledge in action is carried out by subsequent, more methodologically advanced research and performance undertakings – such as the cited practices of Ptasznik.

Case 3: The continuum of Ania Nowak’s work

We cite Ania Nowak’s artistic research practices as an example of crossing the boundaries of choreography in many directions at the same time. In terms of the issue they deal with, they go beyond self-referentiality, and by combining work with movement, text and images, they are a manifestation of the shift of dance practices towards visual arts and the institutions supporting them. Nowak was educated in a patchwork manner: artistically and academically, in Poland and Germany, which certainly influenced her working methods. She graduated in Iberian Studies in Kraków, and then graduated from the Hochschulübergreifendes Zentrum Tanz HZT (Inter-University Centre for Dance Berlin HZT), which she recalls as a major qualitative change that allowed her knowledge and skills to develop in a mature and independent manner (Nowak, 2021; Sosnowska, 2018). Although she has been living and working in Germany since 2011, her projects largely employ Polish art infrastructures (including Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Zamek Ujazdowski, Nowy Teatr in Warsaw, Art Stations Foundation, Komuna Warszawa, Biennale Zielona Góra). Her work placements are closer to the methodological ‘partisanism’ of domestic artistic research than to the ordered paradigm of international artistic research.

The art movement is a research tool for Nowak, while her main area of interest is queer-feminist love, which she perceives not so much as a psychological phenomenon, but rather as a political category, a social act, or a method of producing knowledge (Obarska, 2019; Sosnowska, 2018; Owczarek-Nowak, 2018). Her research process is supported by technology, which she sees as a device for establishing identity and creating social relationships – since 2014 she has been running the technologiesoflove.tumblr.com blog, where she systematically publishes fragments of her research on sexuality, pleasure, emotions and feelings that she conducts in the digital icono- and infosphere36. There, we find excerpts from websites, posts from social networks, videos, reproductions of works of art, her own texts, fragments of scores from other choreographers, literature on the subject, and links to other websites. The blog therefore acts as a transparent notebook, through which Nowak shares and comments on her sources, thus divulging her process of acquiring and organizing research material.

The continuity of the notation testifies to the organic nature of Nowak’s research work and its relative independence from the production problems characteristic of multi-person choreographic productions, such as forced mobility or work in residency, the hardships of which were mentioned by Szymanówka. The realizations prepared by Nowak – solo and collective performances, such as Languages of the Future, Untitled 3, To the Aching Parts! (Manifesto) or Inflammations, as well as entire exhibitions – seem not so much separate projects, but sequential expressions of ongoing research. The artist discloses her applications for scholarships or grants. She emphasizes, however, that the German system of supporting choreographic productions takes into account their distinctiveness, while in Poland, innovative projects of this kind are usually located in the field of experimental theatre, dependent on existing institutions and only partially financed. Nowak draws attention to a research scholarship that can be obtained in Berlin that provides funds for artistic research in the field of dance and movement every year – its intended effect is the creation of new ideas or methods, and not the production of performances (Nowak, 2021).

Nowak often collaborates with Agata Siniarska and Mateusz Szymanówka, and she is a guest performer and creator of her own performances, which she consults dramaturgically and produces in cooperation with invited performers. In the text Mobile Cooperation Networks. Not Only About the Polish Dance Community in Berlin – presenting the background of her own practice – she emphasizes that, in her education, she has assimilated the value of functioning in creative communities but remains critical of its non-hierarchical nature. As she writes: ‘Being a so-called independent choreographer is a constantly fascinating process to me, of critically practising being in a collective and negotiating the roles we give ourselves and others. Currently, it means for me that when working in a group, I avoid idealizing horizontal structures, and I rather seek to consistently cultivate healthy, mobile and soft hierarchies’ (Nowak, 2021). Reflecting on this model seems to be particularly important in artistic processes rooted in the performing arts, which are often abused – as we learn from, inter alia, the current discussion on education in drama schools.

In the project Can you die of a broken heart? presented in 2018 at the Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Zamek Ujazdowski, Nowak synthesized her research as part of a choreographic exhibition. The main research problem was love viewed from the perspective of the relationship between the following orders: the psycho-emotional, the bodily, the socio-cultural and the political. Cardiomyopathy – the title’s ‘broken heart’ – is a heart muscle disease that can occur unexpectedly as a result of a sudden crisis, such as the loss of a loved one. By researching the relationship between health and disease, Nowak broadened the scope of her interests to other conditions, including autoimmune diseases, indicating internal conflict and auto-aggression (Szymanówka-Nowak, 2019; Owczarek-Nowak, 2018).

Using language, she explores the rigorous medical discourse and juxtaposes it with the poetic layer, and then presents it in the form of video performances and performance activities accompanying the exhibition. These sensual, verbal-visual-movement methods of presenting the results of previous analyses of the ways of representing love – or rather the spectrum of emotions, experiences and meanings behind this concept – are, in various discourses, not obvious as the results of research. The artist does not hide her sources, processes, and methods, but they are only available through external channels, such as the aforementioned blog, or interviews. And although Nowak eagerly uses the spoken word in her performances, presenting original speeches, statements, or manifestos, her messages are usually ambiguous, brief, and very literary (Szymanówka-Nowak, 2019; Sosnowska, 2018). And while entering the field of visual arts gives Nowak’s BA activities much greater visibility than occasional performances in theatres, only an intertwining and wide viewing of the messages she produces – exhibitions, performances, interviews, blogs – allows her method of producing knowledge to be perceived. Such a perspective provides insight into her methods based on caring, queering the orthodox ways of seeing the world, and striving for the emancipation of individual experience.

6. Interlacing: problems, potentials, and question marks

In the last part, we look at five ‘interlaces’ – threads related to the development of BA in the context of M/D/CH, which in the course of the analyses particularly attracted our attention. As source material, we used examples collected within the spider-web map, a look at the three cases discussed, a review of literature related to contemporary dance in Poland, as well as meetings with the Pracownia Kuratorska and discussions in the Przestrzeń Wspólna. The presented observations are sketchy preliminary diagnoses that are open to further deepening, solidification, and critical verification. The dominant vectors of our observations are budding associations, emerging doubts, and multiplying question marks.

Artistic work with the movement as ‘self-examination’?

Creative work related to movement/dance/choreography can be considered an artistic study. In this field, the body is treated and understood not only as a tool, but also as a complex (embodied) research and cognitive apparatus37. Perhaps that is why we observe the greatest feedback loop in the research dimension between artistic practice and dance- and movement theory38, not necessarily including other types of scientific disciplines39 (although the exception would be neurocognitive research40; see Frydrysiak, 2018). This is combined with the observation that the BA discussed here in the Polish context focuses in many cases on auto-thematic issues, such as in the case of Research/Production or, partially, the work of Ptasznik. We see here an expression of the need for autonomy – a link with the context of the emancipation of new dance as a field of art (Nowy taniec, 2012; Choreografia: autonomie, 2019).

We are curious as to what will happen when (and if) the inner language of the new dance is discursively grounded. What will be the next ‘riots’ following research not only in the context of self-knowledge, but also of other external problems, as is already starting to happen (e.g. in the context of problems of climate and botany, of social participation or in the political public sphere)?41 How and in what contexts will the research-performative disposition of bodies along with embodied minds be involved?

Exploring collaboration

In M/D/CH research – as opposed to ‘solo generation’ – there emerges a disposition to explore collectivity, which is something other than the joint concept-production-execution work of a team of artistic, technical, and administrative workers towards a performance. This disposition can be observed in the ability to work and communicate with large groups of different potentials and limitations, or in the taking up of topics related to the group’s dynamics: with a common, conscious presence within the group, with a parallel self-analysis of joint action and the relationship between artists and audience. It is also visible in the growing popularity of collective cooperation models, of duets or less binding constellations, where the participants’ orientation is focused on an exchange of skills and experiences, on producing qualities that cannot be accessed alone, and on creating a space for safe development42.

As shown by the Research/Production project, Polish BA rooted in M/D/CH shows an interest in creating cooperative partnerships between a dancer/choreographer and a theoretician/critic43 who, through feedback, look for new forms of self-description and reflection. Another emerging model is the cooperation focused on solving a specific problem, the research into or undertaking of which requires that people with different competences be invited by the project leader44, an example of which is Przyszłość materii (the Future of Matter). Interestingly, when we think about collectivity/community, such practices seem more natural to people in the performing arts, where teamwork has always featured, and not so obvious to people in the field of visual arts or the humanities (as opposed to science, where there is also a distributed work model). This is clearly visible in the practice of Ania Nowak, whose performances are a clear result of consultations and work with the team, while exhibitions appear more as authored artwork.

How can you share knowledge about creating optimal conditions for teamwork, about effective and safe communication? In what scopes and contexts will the practices of inclusiveness and horizontal relations develop (including problems related to power and the institutional context)?

Institutional patchwork, partisans, and outsourcing

For many people involved in movement, education has a partisan-patchwork character. They create their own path of education, which includes specialist tuition (also carried out abroad), and the study of other disciplines – not only those closely related such as art history, theatre studies, dance theory, but also philosophy, cultural studies, and anthropology45. Building work tools in a bottom-up way allows those involved to see new problems, ask questions differently and define directions in a novel way, but it also requires effort and economic capital. It is worth emphasizing that M/D/CH education brings international contacts, scholarships and workshops with it, which is visible in all the examples discussed. It is an environment that, in addition to using domestic experiences and achievements, draws from foreign, especially Western, tributaries, where the problem of creating knowledge through art has been dealt with for over twenty years. A perfect manifestation of this is Ptasznik, who received her choreographic research training outside Poland, and the recognition of the internationally oriented Stokłosa, which led to the initiation of Research/Productionand the invitation to the project not only of Ptasznik, but also of Piotrowska, educated in research in France, and two artists from Finland46, as well as Nowak’s work in Berlin. Thus, it can be observed that methodologically conscious ‘artistic research’ is carried out to a greater extent by people47 who have access to knowledge and experience gained during international academic curricula, workshops, seminars, and studios. This requires appropriate financial, cultural, and time resources48.

We are interested in how the artistic and research infrastructure in dance in Poland will develop further. Will foreign ‘outsourcing’ continue to dominate?

Platforms, projects, programmes, and research scholarships have appeared in the Polish landscape, such as the Stary Browar Nowy Taniec programme – Grażyna Kulczyk’s research scholarship, which Ptasznik used49, or the ‘Choreography in the Centre’ courses of Fundacja Burdąg50. Shelter is sometimes provided by institutions derived from the visual arts, where the research topic is somewhat better established51. The previously explained ‘homelessness’ of dance and its consequences, in particular the lack of stable financing52, affect the nature and scale of the projects implemented here.

What will this mean for BA within M/D/CH in terms of the issues addressed or possible courses of action? Will there be new alliances, or maybe subversive passages dug under existing institutional structures?

Knowledge-exchange formats

How is knowledge shared within dance/movement/choreography? In other words: how are traces left behind53? During the observation and analysis of existing practices, several ‘formats’ or models of knowledge exchange caught our attention:

– Interviews with people working with movement turned out to be a relatively widespread and explored source in the form of interviews and description through conversation. It is a method focused on translating experiences and working methods into another language, here: text, which allows access to knowledge regardless of the time and place of the audience’s presence. Outstanding examples are Mateusz Szymanówka’s Think Tank Choreograficzny54, and the publication Ruchy Oporu by Anka Herbut (2019)55, being the aftermath of the above-mentioned research scholarships, or the publicly funded Choreografia w sieci by Aleksandra Osowicz56.

– Of paramount importance for people associated with dance and movement is participation in shows of work in progress, which allows not only the exchange of knowledge at the embodied level, but also the formation of coupled meta-reflection. An example here is the works in process shown at the Centrum w Ruchu.

– Exchange within different educational models, such as formal education57; artistic-research residencies with substantive support for the artists58, drawing on the experience of other people; a self-education model, i.e. a seminars and workshops – usually available for a fee, such as the ‘Choreography in the Centre’ course conducted by Stokłosa, Ptasznik and Piotrowska; a content-related census as part of laboratory-type projects, such as during research projects in the field of science or closed events at dance festivals such as Malta59, or as part of semi-open support groups such as the Przestrzeń Wspólna.

– Exchange in a personal relationship: access to process notes, choreographic and research journals or scores, individual invitations to cooperation and exchange of competences in the course of production.

Are there any other models in practice? For people not specialized in the M/D/CH field and trying to understand knowledge exchange on the basis of backtracking60, an attempt to answer this question may prove difficult due to the specific system of codes that people working with movement use to communicate with each other. To enter this field and become a part of it, you need to be educated in this direction or have many years of experience – you have to travel, to share your time and space to be part of this world61.

How could BA processes related to M/D/CH open up to knowledge exchange with people not specialized in this particular school62? What is especially worth sharing63?

Empathy within ‘bodies of knowledge’

Recent Polish choreography reveals the postulates of care, empathy, deep emotion, and mutual attunement. Within the social sciences and humanities (see Domańska, 2007), there is a clear need to use methods based on incorporating the body and embodied research64. We see here the possibility of cooperation and of a mutual exploration of methods. Among those currently used, we notice the ‘availability’ potential within, among others: research walks and joint exploration of the environment involving the body; feedback techniques, subjecting to experience and reflecting on both the roles of people participating in the process and the specific interaction between them; and challenging structural divisions (e.g. theory and practice, science and art, action and description) through somatization (see Shusterman, 2016), embodying knowledge and ‘setting it in motion’ to integrate the body into scientific practice.

How can this shared feeling in the space of the ‘body of knowledge’ and accessibility be developed despite the different communication models within the various disciplines of science and art? Would M/D/CH artist researchers be ready to create tools, work methods, or areas of embodied knowledge with the intention of bringing them into a common field?

Conclusion

When we were invited to collaborate on this article, we read the purpose of our activity as creating guidelines for conducting BA in the field of performing arts in Poland. Because we share an affinity for a self-reflective attitude in the acquisition of knowledge, we decided to shift the emphasis to people associated with the field of performing arts in Poland who are already practising BA or are starting to do so. We did not wish to colonize this area of practice by investigating the visual arts nor the Western AR paradigm, but rather to understand what the local specificity is that results from domestic experiences and conditions. We made the decision to narrow it down to M/D/CH practices and we would like to emphasize that the examples presented here are not typical ones and their selection was motivated by the nature of our analysis. We imagine that, on the basis of this text, people with a different background will be able to independently analyse other projects on the spider-web map. We share the backstage of our work and the collected sources to encourage people interested in BA in the performing arts, while looking at foreign BA practices, to seek opportunities to become rooted and to network by producing local ‘seeds’ as well as emerging traditions and helpful infrastructures.

The work on the article also caused shifts in our knowledge and has influenced future directions of interest. First, we plan to continue working on updating the definition of AR. Key observations that will accompany us concern, among others: appreciation of the aspect of ‘self-research’ and emancipation, which has appeared in the field of visual arts but has not been as clear a tendency in the area of M/D/CH with its potential of embodied knowledge; the diverse nature and intentions of subversive activities, and thus their meanings, because the problems related to, for example, institutional infrastructure are varied; and the importance of the inflow of foreign knowledge and experiences in the context of shaping a glocal identity in the field of M/D/CH, where practices self-organize differently than in the visual arts. Secondly, we want to continue exploring the performing arts and raise awareness of BA practices related to its other areas (e.g. theatre or music). Thirdly, as BA researchers, we see the need to develop our own competences and/or to establish further inter- and transdisciplinary collaborations, enabling us to adjust to diverse landscapes. We also intend to continue searching for formats of sharing research results within artistic research studies that would be oriented at various ways of expressing and organizing content. In parallel, we propose a visual-textual narrative on the Research Catalogue platform, which remains a space in motu et flux, as a seed of this search.

Translated by Mark Hoogslag & Tim Brombley

A Polish-language version of the article was originally published in Didaskalia. Gazeta Teatralna 2021 no. 165, DOI: 10.34762/c680-vg85.