Is the State a Choreographer? – Identifying the Origins of Choreographic Power

Abstract

In this article, the author uses the figure of the choreographer as a starting point to identify centres of power in a system in which power is enacted and produced through movement. The author relates Foucault’s theories of state power to contemporary discussions of choreography in dance and performance studies while also drawing on historical understandings of choreography. In the analysis, Gerko Egert’s concept of choreopower (Choreomacht) is extended to focus on cores of choreographic power. Drawing on concepts of Judith Butler, the choreographed body is identified as taking an active part in the actualization of power.

Keywords: choreography; power; choreographer; state; body

Protestors opposing police forces near Lützerath on 10.01.2023; photo: © Unwise Monkeys

Recent academic discourse on choreography has shifted the meaning of the term ‘choreography’ to describe phenomena not necessarily akin to dance. More specifically, the word has been used to describe the political dimensions of the broader field of movement (e.g. Klein, 2013; Foellmer, 2016; Egert, 2022; Mir, 2022). Dance scholar Gabriele Klein framed the choreographic organization of bodies as a central tool for political protest in the public sphere. Furthermore, she established that choreography (understood as a practice directly connected to dance) is always situated within a network of social norms and structures. Klein proposed the concept of social choreography, meaning ‘creating a connection between the social and the aesthetic by attributing to the aesthetic a fundamental role in the description of the political and the social’ (2013, p. 198). Similarly, Foellmer looked at choreography as a medium of protest (2016), examining closely at which point a movement becomes political. A few years later, Egert identified every movement as political and, at the same time, influenced by politics. While the term ‘choreography’ has been applied to theoretical contexts unrelated to artistic dance, the discourse lacks a comparable reapplication of the term ‘choreographer’. In artistic dance practice, if there is a person filling the designated role of choreographer, they always have some form of authority over the choreography and thus over the body of the dancer (Harrington, 2023). The choreography, in this case, originates in the choreographer. With the political dimensions of movement being widely discussed and theorized as choreography, it seems counterintuitive to me to omit the role of the choreographer figure as the source of choreography. This article examines the discourse on political choreography and power through the lens of movement and focuses on the origins of both movement and power. The figure of the choreographer serves merely as a starting point and may later prove to be inadequate.

An introduction to choreographic power

The king, the president and the chancellor – to name just three figures involved in political decision-making – have in common with the choreographer that they enact power over individuals or, more specifically, individuals’ bodies. As Foucault (1991) has shown, controlling the bodies of individuals has long been a key tool for subjecting them to state power. In the late eighteenth century, as the age of public executions was being left behind and the age of discipline was dawning, state power was no longer upheld by eliminating unruly bodies. Punishment, unlike in previous centuries, was no longer a spectacle intended to intimidate the population. Rather, the consequences criminals faced in prisons were designed to address their bodies and reform them as desired. Disciplinary measures concerning the body extended to institutions such as ‘the school, the barracks, the hospital or the workshop’ (p. 140). In his Introduction to Discipline and Punish, Foucault writes,

The body now serves as an instrument or intermediary: if one intervenes upon it to imprison it, or to make it work, it is in order to deprive the individual of a liberty that is regarded both as a right and as a property. The body, according to this penality, is caught up in a system of constraints and privations, obligations and prohibitions (p. 11).

The body has become the site of a power struggle between the individual and those who rule over them. Judith Butler notes that to ‘say it is a “site” is to offer a spatial metaphor for a temporal process’ (2002, p. 15) which is interesting insofar as movement – and by extension choreography – is an operation that is both temporal and spatial. While the focus of this paper is the relation between the individual and the state, it needs to be noted that economic actors also enact control over the bodies of individuals. Training a body to obey, respond and be skilful in specific ways, but also to consume, is imperative to capitalist success. Foucault emphasizes that both the state and capital owners manipulate bodies not only to repress and prevent but also to encourage certain behaviours ‘in order to obtain an efficient machine’ (p. 164). Media and performance scholar Gerko Egert (2022) proposes the concept of choreopower (Choreomacht)

to address the question of power [Macht] from the perspective of movement. Understood as a technique of power, choreography is a method for examining the very constellations of power [Machtkonstellationen] which work with and via movement. Choreography is thereby separated from artistic dance practice in a narrower sense and described as the productive relation of power [Kräfteverhältnis] which brings forth movement and thus affects all movement (Egert, 2022, pp. 117–8, my own translation; for the full German quote see footnote 1).1

Through the concept of choreopower choreography is removed from the practice of artistic dance and applied to all movement. This broader understanding of choreography makes it possible to address power from the perspective of movement and, consequently, address the balance of power inherent to any movement. In a choreographic regime, Egert proposes, power is exercised by controlling the movement of (human, animal and plant) bodies, matter, money and data. The techniques through which choreopower controls movement are themselves informed by movement. As a result of this supposition, Egert avoids pointing towards any instance, policy or system of power that predetermines movement. While I generally agree with Egert’s propositions concerning the concept of choreopower, I slightly diverge from them at this specific point and I argue that there is no choreography without a choreographer. Even if the dancer and the choreographer turn out to be the same person, there is always one who choreographs and one who moves. The concept of choreopower states that every movement is the result of another movement. It cannot be denied that movement encourages further movement, almost like a chain reaction. Equally, I do not minimize the fact that, as Egert suggests, a movement is typically subject to multiple forces which consequently produce a moment of choreographic power. However, I believe that there are centres of power to be identified. It is in those centres of power that I suspect the presence of a figure that, for the moment, I still refer to as ‘choreographer’.

The body as the choreographer’s material

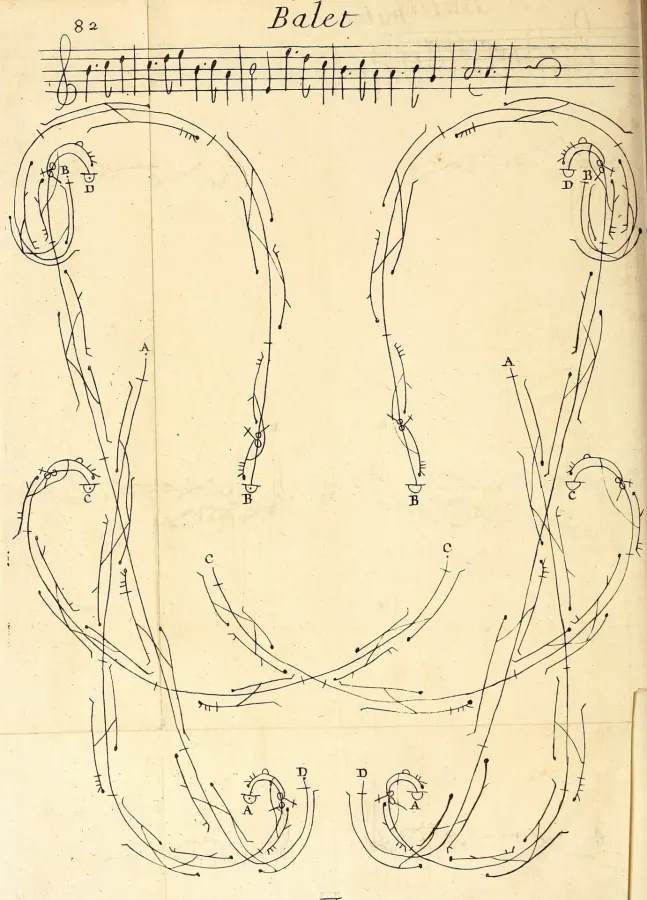

Dance in Europe was captured by choreography at the end of the sixteenth century (Lepecki, 2007). By the seventeenth century the dancing bodies at the court of Louis XIV were completely controlled. Theatre scholar Stefan Apostolou-Hölscher points out that ‘the determination of bodies and their unifying subordination to be one body of the monarch was the original function of ballet’ (2014, p. 159). Choreography meant a system of notation; a representation of movement which was to be precisely replicated by dancers. In the writings of Raoul-Auger Feuillet, who acted as choreographer and notator in late 17th-century France, ‘we are confronted with the idea of a sovereign form inscribing itself into a passive material. […] Resulting from this, in Feuillet there is no space for unruly bodies, their potentials or immanent forms of life’ (p. 159). Being a choreographer meant being in control of every movement performed by dancers. These movements almost exclusively originated in some form of textual notation. The choreographer, however, did not generally think of themselves as an interpreter of these notations. The act of choreographing, from the beginning, was understood as a creative act, as fixating an original idea, creating a score to be interpreted by one or more dancers. The choreographer, not unlike a visual artist or a poet, worked with his material, the human body (Woitas, 2000). Choreographed dance was a case of what ‘Michel Foucault called the classical episteme, in which the representation of reality corresponds point for point with reality itself’ (Franko, 2011, p. 324). The movement performed by dancing bodies was a direct representation of the choreographer’s ideas, which would later be noted on paper. The notation, although descriptive of choreographic ideas, also serves a prescriptive purpose. While the choreographer usually went on to train the dancers’ bodies, written choreography ensures that it may be learned and performed even in the physical absence of its author. While the dancer’s body, the object being controlled, is necessary for the choreography to function, the choreographer’s body, is not. In the centuries that followed, less authoritarian ideas of choreography became established. Apostolou-Hölscher (2014) points to the works of French dancer and choreographer Noverre, written in the eighteenth century, as some of the earliest examples of choreography that was less rigid than a set of rules governing each movement.

Notation from Feuillet’s Recueil de dances (1700)

Dancer and scholar Heather Harrington interviewed contemporary choreographers, who described their didactic-democratic and/or collaborative methods of creating choreography. Those quoted view dancers less as a passive material waiting to be imprinted on and more as fellow contributors to an artistic process. However, as Harrington points out, ‘The dancer gains agency in the fact that they are creating movement, but the choreographer holds the power of accepting or rejecting the movement’ (2023, p. 3). Harrington models a dancer–choreographer relationship in which the two contributing parties are part of an ongoing conversation, constantly influencing each other. She stresses the interpretative nature of dance, highlighting the inevitable deviation of every movement from what was intended. Despite all of this, she still concludes that ‘Dance is a medium where a person can easily fall into being an object – they can lose ownership of their body – how it appears and how it moves, and become alienated from movement that they have created because they are not credited or they lose control of it’ (p. 15). Since Louis XIV, the control of dancing bodies has repeatedly been of interest to those in power. In Christian-influenced states, dancing for hedonistic pleasure is still prohibited on certain holidays. No longer ago than the mid-1990s, the British government prohibited late-night techno raves. Dictatorial regimes issue dance bans or have their citizens rehearse a strict choreography to celebrate their ruler (Klein, 2022). The individuals who dance, however, are not the only bodies addressed by power.

Power and bodies

Michel Foucault notes that ‘power is exercised rather than possessed; it is not the “privilege”, acquired or preserved, of the dominant class, but the overall effect of its strategic positions – an effect that is manifested and sometimes extended by the position of those who are dominated’ (1991, p. 27). Power is not just inherent to any body. It is acquired and upheld through continuous processes. As trivial as it may seem, there are privileged positions in every system, every society, from which it is easier to set in motion and control such power-producing processes. Choreopower (Egert, 2022) is produced through continuous monitoring and control of movement. Uncontrolled movement acts as a threat to state sovereignty, which is why as much movement as possible is regulated. Incidentally, this does not exclusively apply to states ruled by authoritarian leaders or dictators but also to democratically elected governments, which do not refrain from choreographing their citizens.

Drawing on Foucault, Judith Butler notes that ‘to the extent that power forms a body, the body is in some ways, or to some extent, made by power’ (2002, p. 13). The subject and its body are constituted through being continuously affected by power. Butler also points out that Foucault uses the term ‘body’ to refer to both people and institutions. In this open conception of the body, institutional choreography affecting individuals becomes a negotiation of power between (at least) two bodies. The choreography, originating in the (institutional) body of what I have been calling the ‘choreographer’ is confronted with the subject’s body. In this process, the choreographed body becomes a ‘nexus’ (p. 15) – a site where (choreographic) power may be challenged, redirected, transvalued or not affected at all. Power, Butler stresses, does not only happen to the body. The body also happens to the power. In other words, the power of the ‘choreographer’ is actualized only in the body of the choreographed. Choreographic power produces the ‘choreographer’ in the first place and is itself produced by the movement it creates. Similarly, the choreographed subjects are produced by choreographic power, which is in turn only realized through the subjects’ moving bodies. This co-dependence of the bodies, choreographing and choreographed, in producing and upholding choreographic power means that the positions of choreographer and choreographed are by no means static. One could of course use the labels ‘choreographer’ and ‘choreographed’ to describe any relation between at least two parties with an imbalance of power – between student and teacher, employee and employer, or between partners in a romantic and/or sexual relationship. In labelling state institutions and their heads specifically as choreographers, I emphasize that their choreography is usually the most prevalent and therefore performed by broad masses of individuals. As I will show, however, state power rarely originates in a singular body. The term ‘choreographer’, while helpful to label one variable in the relation between someone who choreographs and someone who is choreographed, might turn out to be misleading as it refers to a singular person.

It is at this point that I will address how exactly state institutions affect subjects’ bodies choreographically.

Mechanisms of state choreography

‘Choreography’ etymologically combines the activities of dancing (choro) and writing (graphie) (Franko, 2011). Consequently, with regard to choreographic power, it does not come as a surprise that even though ‘the fact of power precedes the right that establishes, justifies, limits or intensifies it [and] exists before it is regulated, delegated, or legally established’ (Foucault, 2008, p. 304), all instructions of movement issued by a state are written down as laws. The text, similar to the notations created by choreographers in Baroque France, precedes the movement (even if a number of legal texts have come into existence in reaction to movements preceding them). Apostolou-Hölscher even connects the term ‘law’ to the choreographic practice of Feuillet, claiming that at the court of Louis XIV ‘dancers shall merge entirely with the law that is given to them by choreography’s ecriture’ (2014, p. 159). From the moment a law takes effect, every action performed by individuals, even if it contravenes the law, happens in relation to it. Deleuze noted that societies of control had been slowly replacing the disciplinary societies described by Foucault. Instead of training the body to move in a certain way, they are monitoring its movements. According to Deleuze, ‘We no longer find ourselves dealing with the mass/individual pair. Individuals have become “dividuals”, and masses, samples, data, markets or “banks”’ (1992, p. 5). Bodies are fragmented into data on the goods they consume, the money flowing in and out of their accounts, the medical treatments they undergo, the routes they regularly take. Most of this data is available to the state and unavailable data is acquired through forms. The forms themselves choreograph those who fill them out. They do not present an open invitation to disclose facts but, with specific instructions and pre-formatted columns, dictate what information is to be given and in which way.

I focus on the state’s choreography of bodies, but what’s crucial here is the state’s control over the movement of matter, data and money, as bodies are moved by material realities. Any decision on the implementation, extension or limitation of welfare services makes bodies of the poor either move or stiffen. Any approval or ban of medical procedures affects how (and if) bodies can continue to exist. Fences, walls or ditches on one hand and tunnels, bridges and ramps on the other hand physically limit or support movement. An investment in public transportation or a decision to extend a road network determines who can move where and, importantly, how. The state may decide where housing is built and where recreational areas are developed (or at least not demolished) and it mandates which spaces must be accessible to disabled people. These are just a few examples of how movement is controlled through movement (Egert, 2022).

Melkweg Bridge (Purmerend, Netherlands) enables and simultaneosly directs movement of pedestrians, cyclists and boat drivers; photo: © NEXTArchitects

There is, of course, an economic interest in controlling bodies. As Foucault (2008) points out, mobility is an essential element of ‘human capital’ (p. 230). While migrating from one place to another, people do not work (i.e. produce). A population’s ability to make decisions about their movement may also be brought back into economic analysis as the ability to make investment choices. Egert (2022) notes that a constant flow of movement is imperative to any capitalist system. Means of production, human workforce and the goods produced need to stay in constant yet controlled motion to prevent the system from collapsing. Through choreography ‘human activity is captured as labour (which can in turn produce surplus labour)’ (Mir, 2022, p. 22). A state’s choreography, if it works properly (i.e. in the interest of the capital), enables workers movement but guides it enough to result in maximum productivity. Traffic regulations, for instance, decide how fast vehicles (and their passengers) are allowed to move – enabling them to move to their workplaces fast but preventing them from causing traffic accidents. With all commons enclosed, ownership rights regulate which objects individuals may acquire. With ‘the smooth space of nomadism [turned] into a striated space’ (p. 22), stepping on private property uninvited is (in many states) considered a crime. So is stealing and taking somebody else’s life. Criminal codes especially include specific instructions on what to move, how to move and who may move where.

According to Foucault (2008), ‘The crime is that which is punished by the law, and that’s all there is to it’ (p. 251). To use the terminology I propose, a crime is the refusal to follow choreographic instructions. Opposing crime is law enforcement, which Foucault describes as ‘the set of instruments employed to give social and political reality to the act of prohibition in which the formulation of the law consists’ (p. 254). It is one of the mechanisms through which choreography (i.e. the law) is transformed from a notation to actuality. In any state, the police, or in some cases the military, appear as a key element of law enforcement. Moving towards a mass of people, grabbing them, removing them from a space, even hurting them – police bodies physically influence how and where non-police bodies move. The police, ‘through its physical presence and skills, determines the space of circulation for protesters, and ensures that “everyone is in a permissible place” (Deleuze 1995 […])’ (Lepecki, 2013, p. 16). Though in many contexts police are assisted by machine bodies, such as water cannons or guns, the movement their bodies perform is fundamental for their work. As Marc Villanueva Mir (2022) points out, the bodily performance of police is not a mere result of their duties but rather a dedicated technique. Using their bodies, they organize and direct movement while being subjected to choreographies as well. They use choreographic techniques of intimidation, constraint, dispersion and capture, which they constantly train their bodies to perform. Additionally, they too follow the state’s choreography which assigns to them the role of enforcing it. They ‘make move, both as a choreographer and as a dancer’ (p. 26). Their pattern of choreographed movement aims at demobilization, at breaking down movement so that it can be controlled.

According to Egert (2022), choreopower does not only address movement but also the potential of movement. Preacceleration is described as a movement before the actual movement, an impulse that is later actualized when the body changes its position. Choreopower may ignite preacceleration, the mere potential of movement, but also direct it. Foucault proclaimed that by the end of the eighteenth century, ‘the gloomy festival of punishment was dying out’ (1991, p. 8). While public punishment – at least in the European sphere, with which Foucault concerned himself – is not the norm anymore, the rise of modern audiovisual media has resulted in a sort of secondary punishment of public disobedience. Actions of political protesters physically punished by police forces are often filmed, either by nearby allies or media outlets. These recordings then circulate through news media and online networks and, though igniting an enraged outcry, demonstrate what may happen to individuals who do not conform to choreography.

As shown before, the police play an important role in directing movement. The physical presence of the police directly affects individuals’ bodies. But even in their absence the police make bodies move or rather inhibit movement. André Lepecki proposes the concept of choreopolice, which not so much concerns the immediate effect of choreographed movement of police bodies on others as it addresses the subject even without police officers being physically present. The possibility of a confrontation with police forces is sufficient to control the behaviour of the public, Lepecki writes. As long as every body moves along predetermined pathways, in conformity with the state’s choreographic instructions, the police do not intervene. As a result, ‘even without a cop in sight, a daily choreography of conformity emerges, even within so-called free or open societies’ (Lepecki, 2013, p. 20). Choreopolice, while of course related to police, predominantly involves self-policing. The inscribed self-policing has a dual effect: it directs preacceleration and, in effect, results in a movement, and it prevents movement, eliminating preacceleration. Mir explains that for Jacques Rancière ‘the police logic is not defined by the negativity of a reaction but by the positivity of a production: […] For Rancière, the essence of police lies in the production of conformity and normality’ (2022, p. 20). To exemplify the self-policing he seeks to describe, Lepecki (2013) cites Tania Bruguera’s Whisper #5, an artwork performed at Tate Modern London in 2008. Drawing on the historically recurring image of mounted police, the artist had two men dressed as police officers ride on horseback around and through the crowd of visitors, making them move through the exhibition space. None of the visitors disobeyed, even in the safe environment of the museum where they certainly were not going to be punished for their potential disobedience. The work, Lepecki deduces, shows not so much the control of police over the public at the exact moment of confrontation but how the behaviour of the public is already controlled before they encounter the police. Discipline, contrary to Deleuze’s claim, remains a factor in enacting power. Through the repetition of the same patterns of movement in accord with the law, the body is subconsciously trained not to break out of them. Mir (2022) describes the movement resulting from choreopolice as ‘a pacified circulation’ (p. 22).

As enforcement of laws is costly, neo-liberal democracies especially rely on the relative imperceptibility of their choreography (Foucault, 2008). The more citizens realize they are self-policing and notice the mechanisms that direct choreographic power towards them, the more likely they are to oppose them. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the so-called ‘Western’ states imposed curfews, restricted assembly and closed their borders, their citizens were appalled. As the measures were communicated so openly before entering into force, many people became aware of how the state’s power affected their own bodies.2 This example is striking for another reason. As with all instances of choreographic power, citizens were required to comply with regulations. In the case of measures against the coronavirus, the necessity for compliance was amply communicated to the public. States were only able to address the virus with choreographic power if human bodies performed the choreography they were asked to.

At this point I would like to emphasize that a state’s choreography is not limited to its citizens. States, especially in the global north, have a huge interest in controlling which bodies enter their territory and which do not. Additionally, states with significant economic capital have power over the flow of goods, money and data, which affects people all over the world through trade, political agreements or military action. In the case of military action, bodies, just like police bodies, are choreographed in order to move other bodies. Although I focus on states here, I need to stress again that choreography is also influenced by economic actors, even on a global scale. As migration – the movement of bodies – is a significant economic driver (Foucault, 2008), businesses growing into earth-spanning megacorporations create and control movement as much, if not (in some circumstances) more, than states do.

Refusing choreography – moving freely

André Lepecki (2007) considers the dancing body to be limited by choreography. Once dance is submitted to the rule of choreography, he notes, it loses all its power. When dance was placed in the chambers of European courts, it was removed from the public sphere, which transformed a formerly social activity into a project of discipline and subordination. Lepecki appeals to dancers (and academics) to avoid falling into the prison of habit and reinvent their own body on a daily basis instead of repeating the given information (i.e. choreography). What Lepecki calls for here is to cease being a passive target and transform the incoming power into an action, to deny choreography and create something original. Lepecki’s appeal takes on a different meaning if we read it as concerning individuals choreographically addressed by state power. Heather Harrington writes, ‘Dancers are integral to how choreography is performed; they are the choreography’ (2023, p. 4). The same is true for choreographies produced by regimes. As established earlier, power exists through both the power-wielding body and the affected body. As Butler (2002) points out, the French word assujettissement, used by Foucault in his analysis of power, translates to both subordination (subjection) and becoming a subject. Being subjected, it seems, also activates the body. The actualization of choreographic power only happens if the choreographed comply. This opens up the possibility of actively sabotaging the ongoing processes that sustain choreographic power. With their body as the nexus of power, the site where the reality of movement is negotiated, the choreographed may originate new forms of movement.

Dance scholar Susanne Foellmer (2016) examines strategies of counter-choreography in political protests. Protests in public spaces, which literally make bodies move, interrupt pre-choreographed patterns of circulation. Blocking city squares, streets or train rails, protesters use their own bodies to choreograph others, forcing them to find alternative routes, slow down or stop moving altogether. Further, they cancel out the demobilization achieved by the police, providing a counter-strategy to the choreography performed/imposed by police officers. The mobilization of protesters’ bodies, organizing them in space and time in a way that takes up space, is itself a choreographic practice that produces choreographic power. Gabriele Klein (2013) stresses that in talking about political movements the word ‘movement’ should be taken literally as it is a corporeal activity through which political movements operate in the public sphere. In recent years, climate activists from groups such as Extinction Rebellion or Die Letzte Generation (the Last Generation) have impressively demonstrated how choreography may be used as a method of protest. Individuals who glued themselves to arterial roads or chained themselves to trees brought hundreds of motorized vehicles (and their passengers) to a standstill. Infringing multiple laws and regulations, the mere presence of activists near lignite strip-mining sites set in motion the bodies of security staff, police and press representatives.

As demonstrated, the flow of state power heavily relies on compliance. In certain cases, however, compliance has the opposite effect to the one intended. Malicious compliance, otherwise theorized as uncivil obedience (Bulman-Pozen and Pozen, 2015), is a passive-aggressive form of protest that relies on meticulous compliance with a law or regulation. Uncivil disobedience is defined as an act or a series of acts that communicate criticism of a law or regulation with the purpose of disrupting or changing said policy while maintaining legal conformity. Bulman-Pozen and Pozen cite a protest initiated in 1993 by Californian motorists, who challenged the national 55-mile-per-hour speed limit, not by exceeding it, but by meticulously adhering to it. In doing so they sparked general dissatisfaction and, consequently, widespread opposition to the speed limit among fellow drivers. As a further example I refer to Susanne Foellmer’s analysis (2016) of Erdem Gündüz’s performance Duran Adam (Standing Man). In 2013, political gatherings were temporarily prohibited in İstanbul due to frequent protests over the planned demolition of Gezi Park, where a shopping complex was to be constructed. Specifically, the ban concerned any movement as part of a political protest. In response to it, Erdem Gündüz stood still for hours on Taksim Square, facing the Atatürk Cultural Centre. He neither moved nor spoke. In doing so he perfectly complied with the police instructions not to move politically. The police searched him but could not arrest him as standing still was neither a crime nor a violation of the temporary regulations. People joined him, each standing next to him for short periods of time, but no political gathering was initiated, so there was no political gathering to be dissolved. Gündüz, even in complying, not only broke the pattern of no protest choreographed by the İstanbul police but made their bodies complicit in his protest as they stood around him, having realized they could not do anything against the Standing Man.

Erdem Gündüz silently protesting on Taksim Square; photo: © Jwslubbock

There are probably endless possibilities of transforming incoming choreographic power, the simplest of which might be to ignore choreography altogether. Ignoring a prohibition sign, climbing over a fence, stealing some groceries – resistant practices like these are performed every day. Refugees are moved across green (or blue) borders, abortions are performed in secret, documents are forged. Houses are being occupied, medicine is smuggled, graffiti is sprayed. Every migrant entering a country ‘illegally’, every gender-affirming hormone used but not prescribed and every industrial farm broken into denies the choreography intended to prevent these movements. Incidentally, so does every arson attack on refugee homes, every million dollars lost to tax evasion and every swastika staining a public restroom. Refusing choreographic power is not specific to any political conviction. The refusal interrupts a state’s power and redirects it, but the direction depends entirely on the interrupter.

As mentioned before, the roles of the choreographing and the choreographed are neither static nor mutually exclusive. The German Minister of the Interior appears to control a large number of bodies. Yet, he himself is subject to choreographies originating in bodies even more powerful than his. When Alexander Dobrindt instructed the federal police to close German borders for asylum seekers in 2025, critics argued that in doing so he violated European law (Nöstlinger, 2025). While Dobrindt and his ministry have choreographic power over citizens, police and migrant bodies, the choreography in the laws of the European Union is supposed to override the choreography of federal lawmakers. As any other individual addressed by choreographic power, Dobrindt may decide not to abide by choreography and to negate the power supposed to actualize itself in the bodies of both him and the institutions he represents. The minister’s power comes into existence not only through his choreography that addresses others but also through the choreography he does not perform himself.3 Any subject resisting choreography momentarily becomes a choreographer themselves and is, briefly, powerful. A single moment of movement against choreography naturally does not overthrow a state but many counter-choreographic movements, eventually becoming a larger scale movement, might do so.

Cores of choreographic power

I have now extensively described the relations between the individual (i.e. the subject) and the state constituted by movement. Addressing these relations through the analytical frame of choreographic power reveals their fluidity. As choreography keeps bodies in motion, the balance of power in the relationship between the choreographer and the choreographed moves as well. Choreographic power does not produce a static condition but rather ‘a continuous process of negotiation. The world that is being created is the direct result of how bodies move in it and what subjectivities are produced by that movement’ (Mir, 2022, p. 24). Amongst this web of power-producing processes, I sought to identify a choreographer figure responsible for all this movement. As mentioned above, practically any power relation could be examined through this analytical frame. A sign to keep people from stepping on a meadow is, at its core, as much a choreographic operation as is a deployment of armed forces at European borders.4 While it might seem not too difficult to identify the choreographer in a relation between two individuals, the question of origin and responsibility is more complex when applied to a larger-scale movement. The singular form ‘choreographer’ seems an inadequate description for the origin of the choreographic operations of a state controlling a huge mass of bodies.

I have shown in great detail how the state is able to produce and/or control movement, which in turn affects other movement and creates more movement. The position a state occupies in a web of choreographies is what I would call a core of choreographic power. Such cores are characterized by a high concentration of choreographic power. They are produced and sustained because at their (epi-)centre there is one or more (institutional) bodies that affect an extensive amount of movement. And indeed, what we find when we try to identify ‘choreographers’ is that it is not a single person that controls all movement. Rather, we discover an accumulation of movement(s) traceable back to either one specific body or a collection of closely related bodies. And, as has been demonstrated, a state is certainly such a collection of bodies. Made up of multiple choreographing institutions, states have long had a monopoly on controlling movement on a global scale. Not all states possess the same amount of power as the number of bodies they address differs. Depending on the scale, different cores of choreographic power can be defined. On a communal level, each city council and local police station acts as a power core.

While I do not believe that all choreography needs to be evaded (in some cases it may be beneficial to the choreographed), I thought it important to demonstrate the role of power-affected bodies in sustaining power. Understanding the processuality of states’ control over movement and the role choreographed bodies play in the formation of cores of choreographic power is imperative to gaining an understanding of all political movement and the assessment of a need to counter-choreograph.

Wzór cytowania / How to cite:

Kahla, Paul Umut, Is the State a Choreographer? – Identifying the Origins of Choreographic Power, „Didaskalia. Gazeta Teatralna” 2025, nr 190, DOI: 10.34762/esah-nc25.