The Centre for Prisoner Arts: Participants’ Experiences

This article describes the Centrum Sztuki Osadzonych (Centre for Prisoner Arts, CPA), an innovative project developed and delivered in 2022–2023 by Stowarzyszenie Kobietostan (Womanstate Association) at Krzywaniec Penitentiary. The aim of the project was to launch Poland’s first in-prison organization dedicated to sharing experiences and developing methods of rehabilitation through artistic work co-created by prisoners. The work of the Centre for Prisoner Arts, which included women’s and men’s theatre groups, a women’s choir and a band, is discussed here from the perspective of project participants. The study is based on qualitative research based on micro-interviews and it explores the impact of creative activities on participants. Key areas of focus in examining the artistic process included: motivation, group dynamics within the broader prison community, identity, and the influence of participation on the individual’s life in prison – especially in terms of their self-esteem and sense of agency. The research findings helped verify the initial assumptions of the project and provided insights into how Konecka’s and Bresler’s original working method was received. The study also highlights the method’s potential for broader application within the Polish prison system.

Keywords: Centre for Prisoner Arts (CPA); Kobietostan (Womanstate); rehabilitation through the arts; prison theatre; prison music; devising; participatory theatre

Centrum Sztuki Osadzonych, Rita’s Dream: Marcelina, Dominika, Iza, Paulina, Dorota, Kicia, Natalia, Paulina, Nikola; photo: Justyna Żądło

The origin of the CPA

Centrum Sztuki Osadzonych (Centre for Prisoner Arts, CPA) is an innovative project developed and delivered in 2022–2023 by Agnieszka Bresler and Iwona Konecka of Stowarzyszenie Kobietostan (Womanstate Association) and co-created by people working with them at Krzywaniec Penitentiary. The project culminated in autumn 2023 with the opening of Poland’s first centre dedicated to sharing experiences and developing methods in the field of rehabilitation through artistic co-creation in prison (Bresler and Konecka, 2022, p. 7).

The roots of the CPA can be traced back to Bresler’s collaboration with Krzywaniec Penitentiary launched in 2017 and the work done at the prison in the following years by the Womanstate creative collective, co-created by Bresler, and then by the Womanstate Collective Association (now Womanstate Association), founded in 2019 by Bresler, Konecka and their collaborators.

Agency

The immediate inspiration for founding the Centre for Prisoner Arts was Bresler’s and Konecka’s discovery of a dilapidated building adjacent to the penitentiary kitchen.

‘I remember [...] [us] sitting on the balcony talking about this space located in the heart of Krzywaniec Penitentiary, an auditorium [...] [and] that it used to be occupied by the army and could be turned into a venue for the arts,’ says Konecka in Piotr Magdziarz’s film about Festiwal Sztuki Osadzonych (cf. Konecka in Magdziarz, 2023).

While uttering these words, the artist slowed down twice, emphasizing the phrases ‘and could’ and ‘the arts.’ These words encapsulate the paradoxical message of the idea. It was as if articulating a vision of opening a venue for artistic work within an institution of penitentiary confinement, one intended to bring people together, required the speaker to suspend their voice and thus commanded special attention from the audience. Claire Bishop, who put forth a seminal research proposal for participatory projects, discussed an affective dynamic ‘that propels artists to make these projects and people to participate in them’ (Bishop, 2012, p. 5). This affective impulse can be found in Konecka’s words. Presumably, it was related to the artists’ initial realization that a creative space could be added to the topography of a total institution. It is highly likely that the affective dynamic inspired the artists to undertake activities that made it possible for a dream to begin germinating (cf. Bresler in Magdziarz, 2023).

Agency was one of the key notions that the Womenstate co-founders addressed when applying for funding. Looking back on their previous work in penitentiaries, the artists concluded that many prisoners felt ‘robbed of dignity’ and a sense of agency ‘rather than being rehabilitated’ while incarcerated (Bresler and Konecka, 2022, p. 8). Konecka pointed out that after release, former prisoners

would have to [...] manage their [...] liberty, i.e. decision-making, more wisely. When doing time, they are cast as inferior and immature. Everything is provided, [all] hours [...] are set. There is extremely little leeway for decision-making, for sharing in the process of making decisions about anything.1

Therefore, the primary mission of the planned centre was to work towards restoring a sense of agency to the prisoners (‘I can cope with what’s happening to me and have an impact on the things around me’2), coupled with the experience of subjectivity and independence (ibid., p. 7, 9). In the same text, Bresler and Konecka add

The aim of our methods is to make each individual an independent creator, which will strengthen their sense of agency, self-esteem and responsibility for their own and the group’s efforts (ibid., p. 12).

The ways in which the work that would later lead to the founding of the Centre for Prisoner Arts was initiated may suggest that the leaders’ approach agency not unlike the feminist physicist Karen Barad, who believes that ‘agency […] is not a property of persons or things; rather, agency is an enactment, a matter of possibilities for reconfiguring entanglements.’

Barad notes that

in contrast to the usual ‘interaction,’ which assumes that there are separate individual agencies that precede their interaction, the notion of intra-action recognizes that distinct agencies […] emerge through their intra-action (cited in Rick and van der Tuin, 2012b, p. 161).

and that

Agency is about possibilities for worldly re-configurings. So agency is not something possessed by humans, or non-humans for that matter. It is an enactment. And it enlists, if you will, ‘non-humans’ as well as ‘humans’ (cited in Rick and van der Tuin, 2012a, p. 55).

One could hypothesize that if it hadn’t been for the intra-action entanglement of Konecka, Bresler and the artistic wasteland within the prison, the idea of Poland’s first centre for rehabilitation through the arts would not have arisen. The ‘germination of a dream’ (Bresler) about a space like this required the two artists to invite an intra-active entanglement of further elements, in particular the consent of the prison director Daniel Janowski. His approval came at a time when, for political reasons (the rule of PiS in Poland in 2016–2023) initiatives involving rehabilitation through the arts were dramatically curtailed in the Polish penitentiary system. Yet, at Krzywaniec a contract was signed in which the creators of Womanstate undertook to raise funds for artistic and educational efforts and the prison committed itself to renovating the dilapidated building with an auditorium, dedicating it to arts and education and to providing organizational and logistical support for all Centre-related initiatives, including a planned Festiwal Sztuki Osadzonych. This enabled Womanstate to work with Krzywaniec prisoners and liaise with its educators and officers (particularly Ewa Igiel, Natalia Górska and Kornelia Kaziemko). The intra-action entanglements also included partnerships with the Frontis Probation Officers Association and the Zielona Góra-based Teatr Lubuski (Lubuski Theatre).

Bresler’s and Konecka’s symmetrical planning of creative activities for prisoners and of a theatre course for prison educators is proof of their relational perception of agency in the CPA’s efforts.3 The project leaders were not the first people in Poland to recognize that bringing theatre to prisons required systemic change, that is, engaging penitentiary staff as well as working with prisoners and their families,4 but they were the first to undertake a project engaging both of these groups. Providing tools for educators is the first step towards introducing rehabilitation through theatre on a wider scale in Polish prisons. And as far as prisoners were concerned, Bresler and Konecka strove to build agency in the prisoners through art. Conceived in the spirit of the affirmative humanities, the agency was intended to strengthen

the subject and the community […]. In this project, the subject is considered an agent who has the potentiality to […] bring about change. […] It is important, however, not to infantilize them anymore or castrate of their agency (the concept of victim tends to imply passivity on the part of the subject). […] Instead of victimization of the subject, I prefer to speak of their vitalization, i.e. [...] the potential for transformation and surpassing negativity (Domańska, 2014, p. 128).

The two leaders sought to use collective work to enable the prisoners to experience individual and group empowerment and, alongside vitalization, regain the innate potential of transgression and rebirth after going through the negative experiences related to their criminal acts and the resulting penitentiary isolation. This was to be attained through co-creation within the CPA. The planned model not only provided space for co-deciding but made it a necessity.

The process of planning the centre involved a further reconfiguration of entanglements. After Womanstate secured funding for the project, Bresler and Konecka formed a team of collaborators including Urszula Andruszko, Martyna Dębowska, Wojciech Maniewski, Magdalena Mróz and myself. Joanna Kondak, Adam Bąkowski, Izabela Morska and Małgorzata Tyrakowska joined us in the final stages of the project, and a number of volunteers came on board for the project’s final event.

Participation and devising

Over the two years of the project, Krzywaniec prisoners participated in an array of artistic activities. Group participants were accepted on an ongoing basis. Workshops were open to anyone who wished to attend. This policy led to considerable turnover. Five participants were involved from start to finish. Some dropped out, others were released or transferred to other prisons. After completing a course in stage lighting and acoustics, three individuals worked as technicians on two CPA productions, Sen Rity (Rita’s Dream) and Królowie (Kings), staged at the Festiwal Sztuki Osadzonych (27–29 October 2023). About 150 visitors and several dozen prisoners attended performances of two plays and a concert at the final festival in addition to viewing an installation composed of poetry and listening to a broadcast and audio recordings created by participants in radio, journalism and literary workshops.

Centrum Sztuki Osadzonych, the installation and exhibition of poems, audio recordings, and visual artworks, presented during the 2023 Festiwal Sztuki Osadzonych; photo: Justyna Żądło

When seeking contemporary theatre parallels/references for the work done as part of the CPA, one is put in mind of participatory theatre and devised theatre. Both are fit for the CPA’s purpose, that is, the involvement of prisoners in the creative process. From the start, the Centre’s Advisory Board, composed of rotating representatives of all groups, met every three months. During Board sessions, the representatives reported on the progress of work, spoke of challenges,5took part in making decisions on some organizational matters and voiced their needs related to artistic work. In this context, Konecka pointed to a gradation of participation in the development of the plays put on as part of the CPA. She noted that Womanstate’s work process was positioned somewhere in the middle between the role of the director who decides about all aspects of a play and the choices of a collective whose members make all decisions together.6 A similar ‘middle ground’ can be also found in participatory theatre as defined below.

Participatory theatre comprises performance developed in the field of socially engaged art using theatre tools. Creative work in participatory theatre is inclusive and engages the community. To large extent participatory theatre activities reflect the ideas of emancipation through art (Kocemba-Żebrowska, 2017, p. 1).

At the core of this kind of theatre is the idea of the creative involvement of both professional artists and amateurs from ‘specific social groups’ (Bishop, 2012, p. 229).

Konecka emphasizes that she would not work as a theatre-maker in prison if the work did not enable her to grow as an artist. Being creative as an individual protects her from burnout.7 This is why it is so important to strike a balance between collective co-creation and individual original creation.

As for Bresler, her meeting with Jess Thorpe, a lecturer at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, who uses devised theatre methods in hep work in Scottish prisons, was an important inspiration for her theatre work with prisoners (cf. Thorpe, 2019, p. 47–52; Oddey, 1994; Heddon and Milling, 2006). ‘Devising’ is ‘a process for creating performance from scratch, by the group, without a pre-existing script’ (Heddon and Milling, 2006, s. 3). Although creation should be collaboration-based, this does not exclude the presence of a director (ibid., p. 5). Thorpe points out that, in addition to the fundamental values associated with collaboration and co-creation, devising makes it possible to experience different ways of learning in the creative process (Thorpe, 2019, p. 50) and to explore the links between performance work and collaborative creation and the resulting community building (ibid., p. 52). Devising is therefore sometimes regarded as hierarchy-free collaboration, a means to incite social change, even an opportunity for ‘taking control of work and operating autonomously’ (Heddon and Milling, 2006, p. 4–5), which makes it suitable for encouraging and developing performers’ agency. The ethical and the aesthetic perspectives are equally important in Bresler’s and Konecka’s work, as demonstrated by their sources of inspiration and comments.

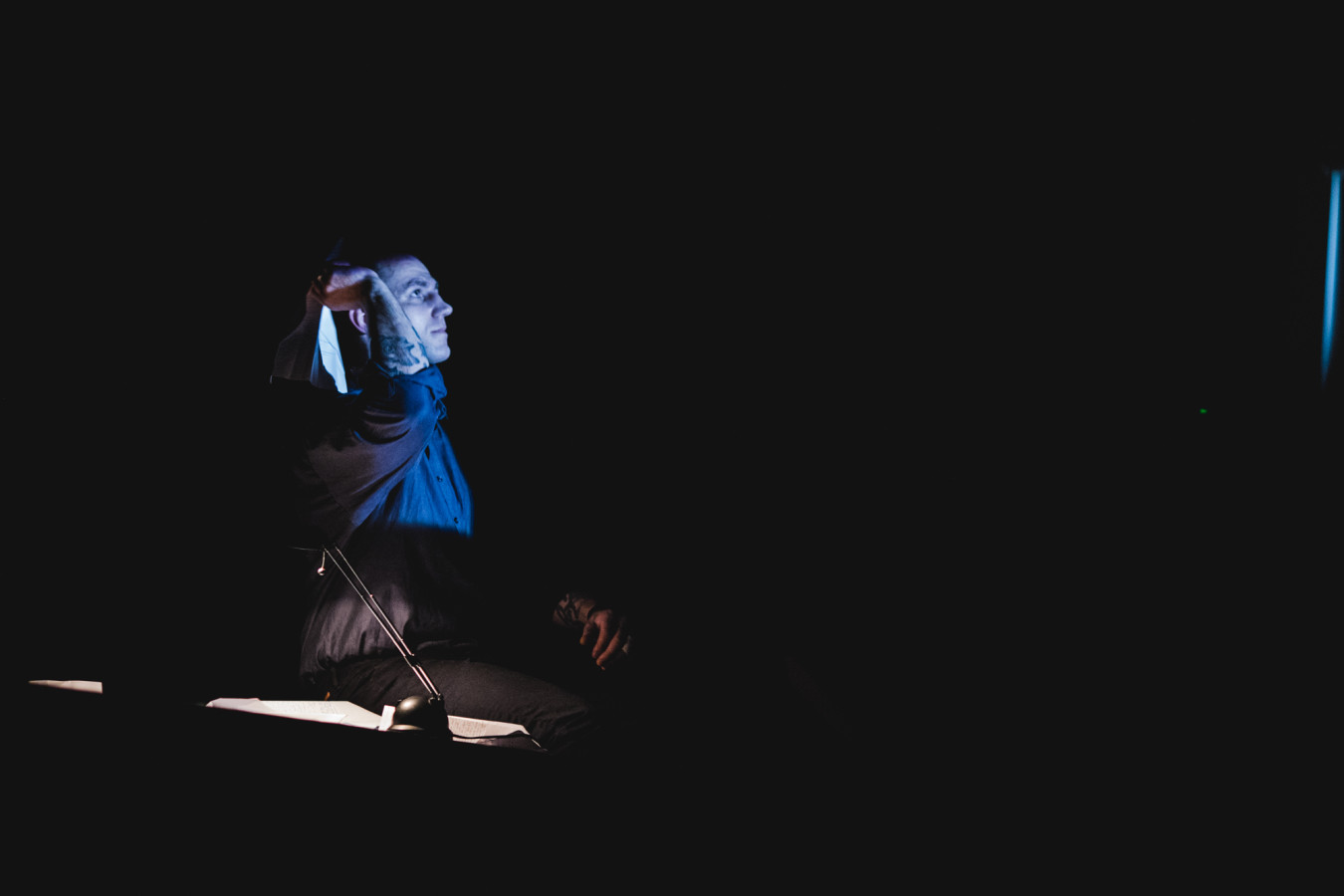

Centrum Sztuki Osadzonych, Kings: Mateusz; photo: Justyna Żądło

It should be stressed here that the goals of the CPA’s theatre groups, band and choir have never been limited to rehabilitation impacts.8 They were always regarded as artistic facts. At the same time, Konecka dissociated herself from the perception of her work in prison as art for art’s sake. Like Bresler, she emphasized that making artistic work is not her sole aim when working with people at risk of exclusion. Rather, she wants to ‘practise responsibility, being in a community, in collaboration, good communication and [the habit of] revealing conflicts’ (Konecka in Kędzia, 2024, p. 88). The idea was to try new things and achieve small successes, strengthening the self-esteem of those engaged in the work.

If the theatre work composed by the two directors affects both its creators and audiences, it is not only due to its high aesthetic quality.9 It is important to stress that the quality is attained by working with groups in a participatory and transparent fashion, i.e. under rules agreed by everyone (the ‘contract’) and using transparent communication. When working with amateur artists, the more co-creation the process involves, the clearer the arrangements need to be. Individuals with little experience of artistic work feel safer working within the bounds of mutually developed rules.10

Research and creation

Bresler and Konecka planned to work with four groups: two groups of women (one with a focus on theatre, the other on literature), two groups of men (also focused on theatre and on literature) and a radio group (which was to collaborate with the prison radio station). In addition, as part of the CPA, they planned to conduct an evaluation via individual interviews with participants from all groups to learn how they perceived their own agency in prison and during CPA activities and their work with Womanstate. The two leaders were keen to explore individual opinions as well as group level communication. Already at the stage of writing the project proposal, a qualitative research component was added to the project, and the leaders approached me about getting involved as an internal evaluator.

Far more interestingly, Bresler and Konecka began their CPA work in early 2022 with a research project initiated by Konecka, but the research work was not programmed in the CPA project. In what I consider a particularly important contribution of Womanstate to the field of community theatre in Poland, the artists blended the CPA’s aesthetic perspective, self-evident for Bresler and Konecka, with a clear inspiration from qualitative research, apparent in the fact that the leaders’ turned their attention to diagnosing the needs of future participants before using their findings ij modelling the planned work. This also demonstrates that intra-action entanglement was in play at every stage of CPA work.

Following in-depth one-on-one interviews with the educators and another conversation with the prison director, Bresler and Konecka met with persons interested in joining the project in all residential units of the Krzywaniec coeducational prison. In their extensive surveys, which involved 90 individuals, the artists asked questions about creation and participation in artistic activities. The interviewees were asked about what skills and abilities they would like to develop and what they would like to do at the Inmates Arts Centre if they were its founders. They were asked what they would like to do most in theatre, writing, visual art, music, radio and journalism work sessions and in a vocational course. The artists also asked more general questions, such as ‘What do you like?,’ ‘What’s your life’s greatest achievement so far?’ (Konecka, 2022). Once completed, the questionnaires served as registration forms for group sessions.

Then the artists held a workshop for individuals interested in joining the project, to which they brought a big sheet of paper with a picture of a river. Everyone was given a smaller piece paper to jot down their dreams, fold it into a paper ship and place it on the river. The initial qualitative research concluded with a creative activity and conversations about the dreams. Evidently, the focus on the process and the ethical dimension did not entail dismissing the aesthetic dimension. The focus was always on these two areas. One included the process, context and relationship, the other creation. Importantly, the initial surveys led the leaders to modify the planned division into groups. Seven groups were formed instead of the formerly planned five: two theatre groups (one for women and one for men); a radio group, a journalism group and a literary group (all three composed of females); a women’s choir; and a band (initially all male). Initially, Bresler and Konecka didn’t intend to set up a choir and a band, but they did so in response to the prisoners’ suggestion. By making changes to the CPA programme to meet the prisoners’ needs, they were the first to consider the agency of participants.

Centrum Sztuki Osadzonych, Sygnatura Akt’s concert: Mirek, Jacek, Natalia; photo: Justyna Żądło

Research as part of creation

Starting in March 2022, Bresler’s and Konecka’s work in Krzywaniec consisted in leading a few days of sessions every two weeks.

The project involved a total of 112 participants (about eleven per cent of the prison population). Twenty of them performed at the final festival. The play of the men’s theatre group incorporated video footage of a few participants who had taken part in rehearsals at some stage but were released before the premiere performance.

Bresler led the work of the women’s theatre group and the women’s choir. Konecka was in charge of the men’s theatre group and she facilitated the work of the band. Each assisted the other in conducting the work sessions.

This practice of mutual support and efforts to ensure each other’s wellbeing in an extremely demanding environment was not part of Womanstate’s work from the collective’s inception. Once discovered, it became a tool that increased the comfort of running the workshops11 and the source of artistic inspiration. The literary group and the journalism group were led by Martyna Dębowska, with Urszula Andruszko overseeing the work of the radio group. Their three groups worked for much shorter periods that culminated in producing a theatre play, a volume of poetry, prose texts and brief broadcasts. Professor Izabela Morska of the University of Gdańsk delivered a workshop for the literary group.

On average, I visited Krzywaniec once every three months, participating in the work of all groups and attending the sessions of the Advisory Board. I took active part in many workshop activities and watched others. My principal task was to conduct qualitative research through micro-interviews that combined elements of structured and unstructured interviews (non-in-depth interviews with open-ended questions). While the structured interviews were designed to collect data in order to explain the behaviour of prisoners in terms of predetermined notions (agency), the unstructured ones eschewed such notions to avoid narrowing the field of research. The research findings were to help verify the initial project objectives, provide feedback about how the work was received and be used by the leaders to disseminate their way of working with prisoners across the penitentiary system. My participation in the project was in keeping with my academic interests.

When working for the CPA, I was spared two challenges typically confronted by field researchers: how to find informants and how to establish good relationships with them and gain their trust (see Fontana and Frey, 2005, p. 710–11). The project leaders did it for me. I was introduced to the participants as a team member and I had no difficulty establishing relationships with them. When conducting the interviews, I followed the same principles I apply to other interviewees. I tried to listen empathetically. The experience from my previous research on prison theatre in Poland proved helpful throughout the process.12 I used a critical interpretive approach in collecting my data (Denzin and Lincoln, 2005a, p. XIV). I tried to remain suspicious (with varying degrees of success) of the excessive affirmation that underpins many artistic community projects and to build an awareness of ‘polyphony,’ ‘perversity, paradox and negation’ (Bishop, 2012, p. 386).

I am not a sociologist by training. I used tools from this field as an autodidact. I combined participant observations with interviews and employed autoethnography tools (see Kacperczyk, 2014, p. 53). My interviews were designed to be conducted as part of the workshops. I was allocated approximately twenty minutes at the end of each session, after rehearsals. The conversations were held in a shared space, with the other participants engaged in activities indirectly related to the project. I talked to participants individually, noting down their answers. I didn’t use a voice recorder because I didn’t have a permit to bring it in and wanted to avoid the tedious process of making transcripts.

The constraints of time and space, including the background noise, had an impact on how comfortable I felt. The most discomforting aspect was the awareness that I had to talk to several people in a short span of time. These limitations, however, didn’t appear to affect my interlocutors. I had good conversations with the vast majority of them and I found them to be open and engaged. I found it more challenging to talk to those who were about to be released and those who were not as interested in the project activities as the others. The conditions prevented our conversations from evolving into longer narrative interviews except for one narrative mini-interview, which occurred beyond my will. Without my prompting, I was told a story of a person’s life in the context of their participation in the project. Susan Chase notes that ‘some interviewees tell stories whether or not researchers want to hear them’ (Chase, 2005, p. 661). It is sometimes the case that by merely talking about an important event one can bring about positive change. ‘Self-narration can lead to personal emancipation – to “better” stories of life difficulties or traumas’ (2005, p. 667–8). During my seven visits to Krzywaniec, each lasting a few days, I conducted 69 micro-interviews with 52 individuals from all groups.

Opening up space

After completing my evaluation of the CPA project, I felt responsible for the voices I was entrusted with. Inspired by Susan Auerbach’s suggestion, I decided to produce and utilize research that ‘can help to create public spaces in which marginalized people’s narratives can be heard even by those who normally do not want to hear them’ (Chase, 2005, p. 669). As an evaluator, I sought to become ‘the conduit for making such voices heard’ (Denzin and Lincoln, 2005b, p. 26), even if they are only fragmentary. This is how the idea was born for writing the text that forms the second part of this article and concerns the participants’ perception of their involvement in the process of the theatre and music work and the work’s impact on them as seen from their perspective. It is worth noting here that my focus will be on the work process, but this doesn’t mean that I dismiss an aesthetic perspective.

My interlocutors were informed that I could use our interviews in my further research work, but they did not authorize them. Hence, I use summaries in some cases, but I don’t refrain from using quotes where I consider them necessary. I have taken extreme care ‘to avoid any harm to them [project participants]’ (Fontana and Frey, 2005, p. 715) and I believe I have succeeded.

For the purposes of this piece, I have organized my research findings around the following topics and issues: motivation to engage in the work, group experience, co-deciding, identity, new experiences and knowledge gained in the rehearsal process, surprises, challenges, and a summing up the work in the context of the project final event and collective performance.

Centrum Sztuki Osadzonych, Kings: Dawid; photo: Justyna Żądło

Motivation

Most of the participants of the theatre and music work sessions joined on their own accord. Some were persuaded by their friends.13 One by his wife. Not all of them had specific expectations, but a few did. The participants were motivated by a variety of factors, including their desire to kill time, to break up the routine of prison life, let off steam, do something for themselves, take their minds off their predicament or find a place where they could feel differently. This is how they explained their participation: ‘I’m part of the underworld. Here it’s different. The art of role-playing – it’s tricking people too but in a different way. […] Here, the audience are the victim’ (Mar.MTG.23.04.2022); ‘I was looking for something, I was behind a mask. I wasn’t myself, I had no purpose. I want to do something for myself, be proud of myself but also […] for my wife and children, and I’m doing just that by taking part in the sessions’ (Mi2.MTG.10.06.2023).

Some participants wanted to work on various mental challenges by practising self-control, patience, assertiveness, overcoming the feeling of embarrassment or shyness. Some joined because they feel good as part of a group, others to learn teamwork,14 still others to gain knowledge or discover a talent. Some hoped to have a good time,15 others were motivated by curiosity.16

A considerable number of participants chose theatre and music work because of their artistic interests and/or experience, or because they wanted to develop theatre or music-related skills. Some had previously performed in prison theatre plays. Others had used to play music or sing and they missed these activities.17 There were also those who wanted to use the time to develop creativity and learn about theatre. A number of individuals wanted to show their families a different side, proving that they were not as bad as others might think.

A female participant – who, together with three others, was involved in the work for the whole duration of the project from 2022 to 2023 – said in April 2022: ‘I’d like to work on strengthening my self-confidence [...] so my parents can see me in a play like this. I’d like to surprise them’ (D.WTG.22.04.2022). After months of rehearsals, during two days of performances (of the plays and the work-in-progress concert) by the four CPA groups in December 2022, staged for fellow prisoners and outside visitors, the same woman said: ‘We’re more open now. The work has strengthened my self-esteem. My loved ones – my parents, my husband – are proud of me. I’m proud of myself. I’ve overcome tons of inhibitions. It gets easier every time I perform’ (D.WTG.09.12.2022).

The group

For many people, their involvement in the work, particularly in the theatre groups, involved overcoming inhibitions or shyness/embarrassment. One participant admitted that he had to work on his self-control to be able to take part in the work (A.MTG.3.09.2022). Some felt nervous and feared criticism when joining a group whose work was already in progress. Others were appreciative of being accepted by close-knit groups. Some female choir members were especially adamant that no one should be excluded, even those who attended the sessions irregularly (including mothers of young children), so they found them a niche as background singers (Ani.CHK.02.07.2022). Regular attendees argued that even attending a single session was valuable for such persons. ‘Singing […] is good for mothers with babies, they can take a break’ (Wer.CHK.02.07.2022).

Many participants of the theatre and music groups acknowledged that there was a friendly atmosphere during work sessions and that the group members got on well with each other. This helped one participant to gain self-esteem. Another said she experienced friendship in prison. One actor said that ‘In prison I have mates. In the theatre group, I feel like we go back a long way, even though we first met a week ago’ (An.MTG.09.12.2022). In two consecutive interviews conducted over a span of eight months, a co-founder of the women’s theatre compared the group and its leaders to a family (A1.WTG.22.04.2022; A1.WTG.09.12.2022).

The following observation by a member of the women’s choir is particularly relevant in the context of my involvement in the project: ‘The work helped us build relationships with each other. We’ve grown closer. There’s more trust and support between us’ (Mar.CHK.09.12.2022). Building this sort of relationships in prison is potentially transformative. Many participants described mutual help and collective support as a particularly significant experience.18 When one of the theatre members was about to drop out, her friend from the group, known under the alias of Motyl (Butterfly), asked her for help in rehearsing her part by saying other performers’ lines to complete the dialogue. This was a ruse that led to the person rejoining the rehearsal process and performing in work-in-progress shows. Experiencing respect19 and rebuilding trust in people20 were regarded by many participants as equally important as help and support. The group contracts agreed at the start of the rehearsal process were instrumental here. Some participants said there were no conflicts within their group.21 Others didn’t deny that conflicts existed, but they said that they were learning to resolve them.

Opinions on the differences between how participants functioned in the CPA sessions and in their units varied. While some discerned no such differences, many others viewed the two environments as polarly opposed. It was repeatedly stated that prisoners tended to have contact with only one or two people in the prison units, whereas during CPA sessions they could talk freely with anyone. It was pointed out that the hallmarks of the groups included friendliness, mutual encouragement and positive criticism that did not cause serious upsets (Il.WTG.10.06.2023). This contrasted with the units, where participants experienced mean treatment. Many individuals felt more relaxed and joyful during their work sessions.22

One of the theatre co-founders cited two reasons for the differences: ‘There are different people in the work sessions and different in the cell. Here we work together, we’re in motion. There we sit. There’s stagnation’ (N.WTG.10.06.2023). This diagnosis seems correct, because the CPA sessions were attended by those for whom their daily prison experience wasn’t sufficient. The opposition of movement during rehearsals and immobility or very limited movement in cramped cells is an interesting topic for possible elaboration. It is no coincidence that serving time in prison is colloquially referred to as siedzenie (sitting) in Polish.

It is interesting to note that despite the differences between the prison units and CPA rehearsals, an interaction between them developed. A choir member said she had brought a song from the rehearsals to her cell and everyone in her whole cell started to sing Cementerio (Patio de Godella).23 Another choir member performed the song in her workplace. Yet another said that what happened in her rehearsals was an important topic of conversation with her co-prisoners (mothers with children up to three years of age). A degree of osmosis, fashioned by the prisoners, developed between the CPA and the prison.

The CPA group work inspired several individuals to begin artistic collaborating outside the project. They started to believe they could achieve something together, which strengthened them.24 One of the choir members noted: ‘I see that despite our differences, the girls in the choir and I have something in common. […] When we are together, there’s power. Each of us brings something different. A group is more powerful than one person’ (I2.CHK.09.12.2022). Her friend addressed the integration process: ‘With each new session […] we gradually open up. There’s a growing understanding among us. The sessions bind us together. It takes time to open up’ (I1.CHK.09.12.2022). The band leader made similar comments: ‘The process of connecting with each other is important […]. For us, art is a challenge but also an opportunity to do things together, collaborate, deepen our relations, resolve conflicts, develop talents’ (S.BD.09.12.2022).

Centrum Sztuki Osadzonych, Rita’s Dream: Magda, Kicia, Iza, Nikola, Paulina, Ilona, Dominika, Zosia; photo: Justyna Żądło

Co-deciding and agency

In my interviews I also asked about the CPA’s mission of restoring a sense of agency. Most participants contrasted the CPA with the prison. They emphasized that during rehearsals they could make decisions and propose initiatives, even if some of the decisions and initiatives were not accepted by the group.25 The interviewees said that the group leaders, unlike the prison wards, respected their opinions. ‘Here our voices are heard,’ said a choir member. ‘We are listened to. We are asked questions […] and that gives us freedom. We feel we matter. We are women, not prisoners’ (L.CHK.04.09.2022). Others shared similar observations. ‘In prison we can only ask. Here we can do something or not – we know that we can refuse and that expands our perspective,’ said a female actor (And.WTG.22.04.2022). Another choir member pointed out further differences in decision-making: ‘Decision-making in the group and in prison are a world apart. Here [in the work sessions – M.H.] the artistic soul matters. There [in prison – M.H.] you’ve got to be strong. If you show you’re weak, you’re done for. Here it’s easier to be yourself. We can show we’re sensitive’ (I1.CHK.04.09.2022).

Despite the contrasting opinions, the same person said that she and her friends took what they learned back to their cells. At the prompting of the leaders, some participants (mainly the band members) worked together independently of their leaders between work sessions. In addition, the theatre and choir participants did a number of things on their own initiative (including painting a cat for the hospice). One woman attributed her newly gained agency to the influence of the theatre: ‘Theatre has taught me how to do things – to move forward, pursue my goals. Leave the past behind’ (S.WTG.09.12.2022). Many other participants expressed similar sentiments.

Yet there were also prisoners who believed that one could make their own choices in prison too and that if there was will, one could do things that mattered to them (Mo.WTG.22.04.2022). Such voices, however, were rare.

Shaping identity

One of the problems of convict rehabilitation in Poland is the fact that prisoners’ complex identities tend to be replaced with a label indicating their social position. The criminal acts they’ve committed not only start to define their core identity but also reinforce and fix it (cf. Hasiuk, 2015, p. 222).

This is why it’s so important to inspire individuals to build their own identities based on other activities. I raised this question in my interviews, assuming that through the experiences of decision-making and agency, participants of the artistic work can discover new social roles as CPA co-creators and use these roles in building an identity other than that of a prisoner. When asked whether they felt to be co-creators of the plays, many of the theatre and choir members I interviewed answered in the affirmative. Even if some found the word ‘co-creator’ problematic, they noted that they contributed their voice (I2.CHK.09.12.2022), their active role and felt important: ‘Each of us mattered here. This is our hard work. The theatre work and rehearsals, which we did for the first time, were a challenge for us, but we succeeded. I’m proud of all of us, proud of the fact we were afraid, but we worked’ (D.WTG.09.12.2022). The participants spoke of their sense of responsibility for their collective work and their desire to develop it (L.CHK.09.12.2022).

‘These sessions awaken normality’

In addition to producing theatre plays, a music concert, texts, recordings, and an in-prison theatre space, the aim of the CPA work was to allow participants to gain experience. The following two questions encapsulate two other topics raised in our conversations. Have the work sessions given their participants anything? Have they learned something new about themselves?

The participants’ opinions on whether activities such as the ones offered by the CPA are needed in prison ranged from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘no opinion.’ According to my observations, in order access a broader range of experiences, participants needed to overcome their scepticism and fully engage in the work.

Many participants pointed out that the sessions took their minds off them being in prison. The rehearsals felt like so many hours of freedom.26 ‘I feel open in the sessions, closed on the block. They don’t even have a shrink you can talk to,’ complained one of the female actors (S.WTG.09.12.2022). The experience of freedom in prison meant freedom of speech, freedom of spirit and freedom of mind for the participants. The artistic work was also the source of existential support: ‘the music work lifts my spirits, keeps me from thinking about how much time I’m going to be here […] and to fight for every day, fight to get up in the morning’ (I2.CHK.09.12.2022); the sessions help prisoners not to lose themselves in the prison reality (Mi2.MTG.10.06.2023); they structure time and make it easier to live between sessions (Mt1.MTG.10.06.2023).

Bresler and Konecka are not therapists, but they make use of theatre and music tools, theatre pedagogy tools, group processes and individual aptitudes. Workshop participants noted that the artistic work allowed them to overcome numerous internal barriers.27 They also spoke of the psychological competences they had gained through rehearsals, such as greater openness to people and new situations,28 higher confidence,29 courage,30 reduced anxiety, experience of peace, feeling recharged,31 lightness and happiness induced by appreciation.32 The theatre work gave some participants self-esteem.33 (Z.WTG.11.11.2023). A woman whose family and friends had often told her she was talentless said: ‘Now I can prove to my family that I’m worth something, that I’ll be of use’ (Z.WTG.11.11.2023).

Far more interestingly, some of the effects of the artistic work were identical to those of therapy. A female actor said: ‘This work has made me feel much better, I don’t feel bad emotions. I’ve learnt not to take everything personally […] [I’ve learned how – M.H.] to tell the difference between emotions. I know I have emotions and I know when I’m afraid, when there’s sadness, joy. I didn’t know that before’ (S.WTG.09.12.2022). One male actor pointed to the sense of strength brought about by progress in the theatre work. Rehearsals enabled him to release emotions and get rid of stress (D.MTG.10.06.2023). Others became aware of their own competences and the benefits of working on themselves. Discovering creativity in themselves and others was an important aspect of the work. At the same time, there were those who claimed that they hadn’t learned anything new about themselves during the workshops (A2.WTG.09.12.2022).

Rehearsals helped many of the participants gain or develop various skills. One female actor confessed that she had used to have a fear of speaking in public, but it vanished after the rehearsals (As.WTG.01.07.2022). Another noted that ‘confidence grows when you learn so many lines by heart,’ adding that she enjoyed herself. Most of her part was her idea (Na.WTG.27.10.2023). Some participants found it easier to talk about themselves after the workshops. They learned new ways of working with their voices, practised mindfulness and paying attention to gestures, situations and the presence of others, confronted acting challenges and overcame their anxiety about reading aloud in public. They also learned how to give a massage. A book-loving actor appreciated the inclusion of Shakespeare’s work in the rehearsals (Mt2.MTG.10.06.2023). The leader of the band Sygnatura Akt (Case Number) expressed his gratitude for being able to write music and lyrics and to share them with people he knows. The band influenced his everyday life: ‘Now, with Jacek [his bandmate – M.H.], we rehearse, record music and play it back every day. […] Sometimes I spend half a day playing guitar’ (S.BD.09.12.2022). Natalia, who after 18 months of working in the women’s choir became a singer in the men’s band – which seemed impossible at the start of the project due to the lack of consent on the part of the prison authorities – said about her new challenge: ‘It was hard at first, an unknown. Now [after five months of rehearsals – M.H.] I feel braver, appreciated and fulfilled. I used to sing [on stage – M.H.], but I never sang heavy stuff like this. This is what I’ve learned’ (N.CHK.11.11.2023). Their artistic work motivated participants to work on their values and not revert to what they did when they were free. A musician briefly involved in the band’s rehearsals commented that the presence of leaders who brought passion to art and life, and a clearly defined objective, make the CPA a space that could ‘bring growth’ (A.BD.10.06.2023). His bandmate felt satisfied with his work, which motivated him to improve (S.BD.11.11.2023). The band’s first singer, who was also an actor, shared similar observations. He noted that regular theatre and music rehearsals helped him develop responsibility, assertiveness and discipline. They taught him to start from what is possible, from the person himself. Unlike the laziness and criticism that often dominates in prison, ‘here [we have] an open mind, an open heart, creative use of time. Many positive values’ (D.BD/MTG.03.07.2022). One of his fellow theatre members said that he did more for himself during three work sessions than he had done for four and a half years of his time in prison. ‘These sessions awaken normality [...] we learn ease, heart, sensitivity’ (Mi2.MTG.10.06.2023).

Centrum Sztuki Osadzonych, Sygnatura Akt’s concert: Sławek, Iwona Konecka (guest appearance); fot. Justyna Żądło

Surprises

What participants found most surprising about the CPA was the commitment exhibited by outsiders, collective creation of something valuable, and the relations between the work leaders and participants. Comments included: ‘here they are interested in us’ (To.WTG.03.09.2022), ‘they don’t hold us accountable for everything we do’ (I1.CHK.04.09.2022), ‘they don’t condemn us’ (L.CHK.09.12.2022). ‘At last, someone looked at us as human beings at the CPA’ (S.BD.11.11.2023); [during rehearsals – M.H.] ‘I was treated normally, like a free person. […] I felt someone supported me, was behind me, respected me’ (D.WTG.09.12.2022); the leaders ‘looked at us with compassion, and that opens the heart’ (I2.CHK.09.12.2022). One of the choir members concluded:

It helps prisoners a lot to know that someone on the outside [...] tries to figure out how to help us. The leaders did a massive job. We feel we’re not alone. The participants [of the CPA – M.H.] discovered, confirmed, that they’ve each got their own personality, individuality. The leaders’ involvement proved this. They made us realize we’re worth something. Their influence made it happen (D.WTG/CHK.11.11.2023).

Some participants pointed out that praise and appreciation propelled them to work. The way the tasks were suggested made them feel safe and able to open up.

The choir members pointed out that the work sessions would support them after release: ‘Caught up in the cycle of stealing and doing drugs – here [during rehearsals – M.H.] you can see that there are people in the world’ (L.CHK.04.09.2022). ‘These sessions give hope for a tomorrow. I see a good world. I don’t see lost people […]. The sessions are an escape and proof that a normal life is out there’ (Ani.CHK.02.07.2022).

Challenges

For most participants, the project was a big challenge and a commitment to a new field. The men found it easier to talk about the challenges, which stemmed from organizational issues, including high participant turnover and, especially early on, uncertainty as to whether participants would be escorted to the sessions.

The latter happened only rarely and was due to the prison staff’s excessive workload, occasional disruptions in the flow of information between prison officers, or omissions. Because of high participant turnover in the men’s theatre group, Konecka had to significantly change the play’s composition and modify its structure by including a video component. Some changes in the group composition caused friction, but this isn’t something I witnessed often. One participant expressed disappointment in his fellow prisoners who dropped out after attending a number of rehearsals: ‘I don’t know what people really want out of these sessions’ (Mt2.MTG.10.06.2023). Some felt overwhelmed by their fellow prisoners’ contempt at them taking part in rehearsals.

Centrum Sztuki Osadzonych, Kings: Dawid, Mateusz; photo: Justyna Żądło

Another set of challenges concerned the theatre work itself. Some participants found it difficult to grasp the theme of the plays, deal with their lines, or find a part they could identify with. Completing the tasks suggested during rehearsals, getting into character, and stage fright before the show also proved challenging.

The audience’s reaction was the source of another type of anxiety. Questions were asked. Will the actors get a positive reception? Will they face ridicule? Will they stick out unfavourably against other members of the cast? Will they seem too stagy? For some the challenges proved so steep that they gave up rehearsals. Most of them did not seek support from the leaders. Yet there were also individuals who continued despite considerable difficulties and expressed satisfaction at the end of the process.

From the perspective of the final event

When asked about the impact of working with Womanstate from the perspective of the final event and the final gathering of all groups, several participants gave complementary answers.

One of the three performers in the play Kings considered his involvement in the CPA sessions to be the greatest challenge he’d ever confronted. The actor contemplated leaving the project more than once but was happy that he stayed until the premiere show, which enabled him to discover the value of keeping his word. The new experience made him more open and more communicative, he learned to work as part of a team and not fear challenges. The rehearsals affected both his daily interactions in prison and the relationships with his loved ones. His self-esteem and inner strength grew. He succeeded in overcoming his stage fear and noticed that he found it much easier to perform in front of an audience of strangers (Mt1.MTG.10.11.2023).

A performer in the play Rita’s Dream confessed that the rehearsals helped her find the motivation to fight for what mattered to her and not give up. She learned acting skills and improved her self-esteem. She stopped giving up easily after developing a fighting spirit. She used to be too trusting, but after engaging in the collective work, she gained distance and self-confidence. When she doesn’t want something or is not going to do something, she is open about this. She isn’t submissive. She wouldn’t describe herself as assertive, but she strives to become so. The CPA enabled her to reclaim her own voice (Il.WTG.11.11.2023).

A younger participant felt extremely appreciated after the show. She’d never thought her performance would be so well received. Her self-belief grew and she gained some distance to herself. She delt with her pre-show stress on her own, discovering the power of dance and breathing. She expressed her desire to keep learning and developing, including artistically, when the project is over (Na.WTG.11.11.2023).

The CPA work helped one performer in the women’s theatre and choir to overcome her fear. She decided to perform on stage to prove to herself that she could do that. She is a secretive person. For her, the theatre is something different. It brings her great joy and she feels a surge of energy after each show or rehearsal. The work also helps her to connect with others. The steps she’s taken have helped her become more confident. She is now ready to do something, which was not necessarily the case before (Ki.WTG/CHK.11.11.2023).

After the project ended, the choir member who became the band’s singer said: ‘I don’t have that disbelief [anymore]. I feel a stronger sense of responsibility. If I don’t come to rehearsal, others won’t be able to work. I feel needed and part of a community; I have more confidence in myself and my own opinion. Before, when I had something to say or disagreed with something, I kept this to myself. [At CPA – M.H.] I’ve learned to speak up and set boundaries. The work taught me that I don’t have to be quiet. I’ve experienced the power of women’ (N.CHK.11.11.2023).

After the performances

The shows at Festiwal Sztuki Osadzonych and the recording of a music video by the band played an important role.34 They were not merely the culmination of the work or an opportunity to show its results to other people, including the prisoners’ families and prison staff representatives. The theatre shows, the concert and the music video were seen by their creators not only as an expression of collective strength, a source of satisfaction or a shared success but also as a way of repaying for the confidence placed in them. The focus of the actors and musicians on something other than themselves can be perceived as an expression of transgressive potential (cf. Frankl, 2010, p. 39). The appreciation of the audience and work leaders35 as well as self-appreciation within and between the groups had a strong positive effect on all participants (J.BD.11.11.2023). This is how one musician described his experience as a spectator: ‘[I was – M.H.] hugely impressed by the men’s theatre. The women’s theatre provoked emotions. I was moved at the end [...]. It’s been twenty years since something like this happened to me’ (J.BD.11.11.2023).

My research demonstrates that the CPA’s objective of increasing the agency and self-esteem of the project participants – at least those who co-created the festival or were strongly involved in the project at some stage – was attained. It shows that something else, equally important, was also achieved: the participants succeeded in building closer interpersonal relationships. ‘This project has taught me to connect better with people,’ admitted the leader of Sygnatura Akt. The participants spoke of a ‘sense of community,’ an experience of integration and how, through the activities, individuals found ‘support in each other.’

Konecka and Bresler supported each other in their work as co-leaders. Working with the groups in a transparent, co-responsible and non-hierarchical manner while exhibiting care (for themselves and others), they established a model relationship, which was later adopted and developed by the participants without the leaders’ involvement.

This is how Dariusz Kosiński defines a theatre company/ensemble:

a group of theatre-makers working together for a longer period of time [...] and forming a community united by a peculiar bond. The fact that a theatre production is the work of many artists leads to the assumption that all those involved in its creation should be united by a sense of responsibility and, at the same time, they should work closely together for the good of the whole [project]. [...] The condition for the emergence and longevity of a theatre company/ensemble is a community of ideological and artistic beliefs, or – at least – trust in the group leader, a belief in the value of his/her ideas and actions. Further consequences include a community of style and mutual inspiration to undertake intense artistic work (2009, p. 223).

For the most part this definition can be successfully applied to the work done as part of the CPA. Furthermore, the work embodied the principles of the affirmative humanities36 and inspired situations in which individuals (at least some of them) could experience self-transcendence (Frankl, 2010, p. 31).37 It therefore had an impact both in the social dimension and on a deeply personal level. One of the reasons why this this subject is difficult to write about is the fact that after Bresler and Konecka left Krzywaniec, the agential entanglements and intra-actions they had set in motion ceased to operate as they had before. Having completed their project (financed with funds they had raised), Bresler and Konecka wanted to continue the collaboration as part of another European project, but their idea was not accepted by Krzywaniec due to its director’s retirement plans. Moreover, the renovation of the prison staff hotel building that Womanstate used for their work would significantly complicate the logistics and increase the cost of further work. After a hiatus, Womanstate will return to Krzywaniec for a few days in autumn 2025 with the participants of the ‘Theatre that Breaks Down Walls’ course, who want to work with the prisoners. A second instalment of Festiwal Sztuki Osadzonych is planned for 2026.

Centrum Sztuki Osadzonych, Rita’s Dream: Dorota, Dominika, Nikola, Iza, Zosia; photo: Justyna Żądło

Regrettably, the unique practice of the CPA has not yet inspired a transformation of penitentiary work in Poland. No efforts have been made to make such initiatives part of the systemic solutions supported by sustained funding. Krzywaniec Penitentiary uses the name Centre for Prisoner Arts and the space regularly hosts music performances, theatre shows, lectures and public discussions with invited guests. However, prisoners are rarely seen on its stage, which was the purpose of the Centre. The members of Teatr Lalka w Trasie (Doll On Tour Theatre) would come to Krzywaniec for some a period of time, which resulted in the development of two new plays with female prisoners, but this collaboration came to an end, too.

The CPA co-creators remaining behind bars cannot continue their work in a form similar to that introduced by Bresler and Konecka. A number of them expressed a strong desire to do so, but the prison officials did not give their consent.38

I was leaving my job at the CPA with the following words on my mind – spoken by an CPA co-creator in reply to my question ‘What would help in prison?’ – ‘Someone who’d listen attentively’ (And.WTG.22.04.2022), and with the goal of making initiatives such as the Womanstate-run Centre for Prisoner Arts a reality in Polish prisons.

Translated by Mirosław Rusek

Niniejsza publikacja została sfinansowana ze środków Wydziału Polonistyki w ramach Programu Strategicznego Inicjatywa Doskonałości w Uniwersytecie Jagiellońskim.

This publication was financed by the Faculty of Polish Studies as part of Strategic Programme Excellence Initiative at Jagiellonian University.

A Polish-language version of the article was originally published in Didaskalia. Gazeta Teatralna 2025, nr 186, DOI: 10.34762/rc0z-7249.