Infrastructural Intermediality as Institutional Choreography: Contemporary Dance and Visual Art Institutions in India

Artykuł powstał jako odpowiedź na call for papers Choreografia a instytucje. Problemy, diagnozy, studia przypadków pod redakcją Zuzanny Berendt, Alicji Müller i Izabeli Zawadzkiej. Cykl publikowany jest od numeru bieżącego numeru. / The article was written as a response to the call for papers Choreography and Institutions: Issues, Diagnoses, Case Studies, edited by Zuzanna Berendt, Alicja Müller and Izabela Zawadzka. The series is published from current issue.

Abstract

This article examines the migration of contemporary Indian dance into visual art infrastructures, theorizing this shift through the concept of infrastructural intermediality – a form of institutional choreography where economic systems, spatial architectures, and curatorial protocols shape choreographic form, labour, and spectatorship. Drawing on genealogies of Indian modernism, the performative turn of the 1990s, and the rise of alternative art spaces, it situates the Kochi-Muziris Biennale as a paradigmatic case of institutional improvisation. A case study of Padmini Chettur reveals how re-skilling for exhibition contexts (re)defines contemporary dance aesthetics while exposing neoliberal and caste-class hierarchies that choreograph visibility, value, and precarity in India’s cultural economy.

Keywords: contemporary Indian dance; infrastructural intermediality; institutional choreography; Kochi-Muziris Biennale; neoliberalism; caste; visual art institutions

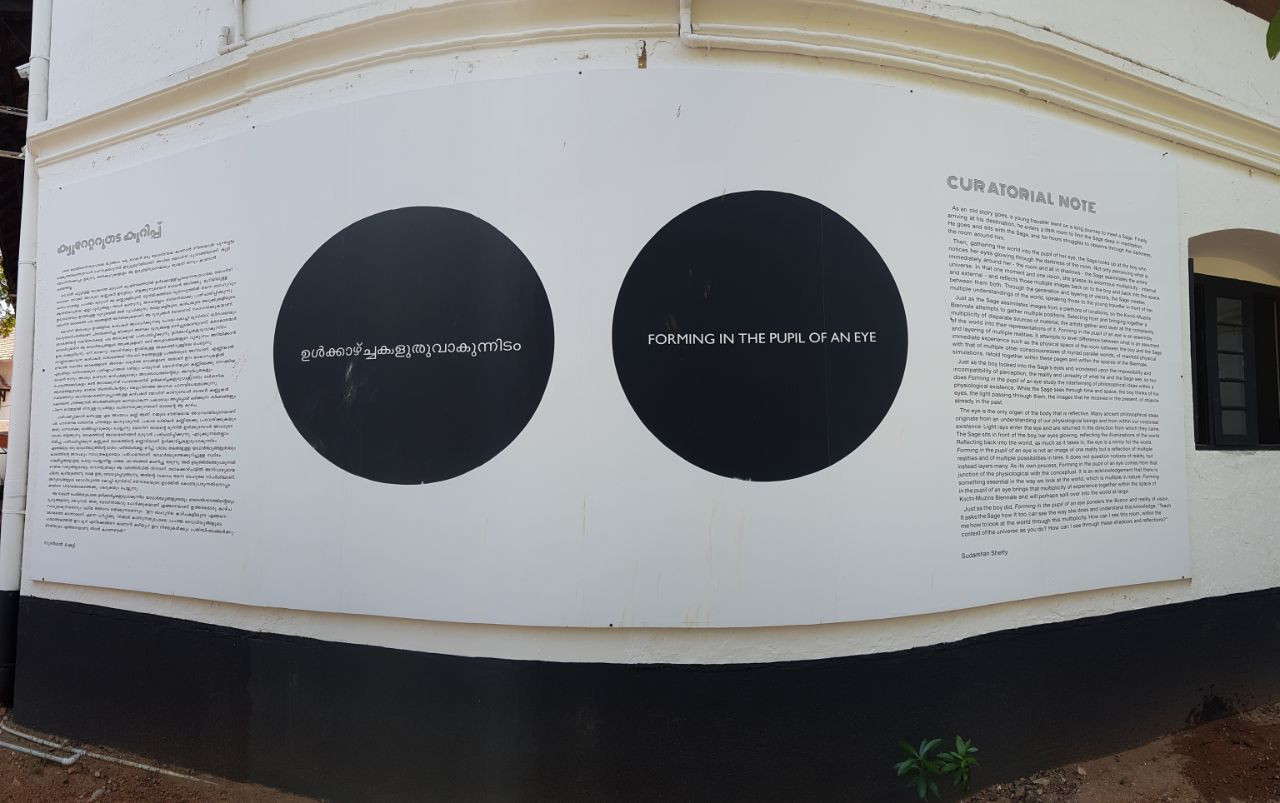

Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2016, Curatorial Note; photo: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

Introduction

At David Hall, a seventeenth-century Dutch bungalow turned gallery in Fort Kochi, five dancers lean forward in unison. Barefoot, their bodies angled just off wooden chairs, they balance on the arches of their feet: right hands lifted in hamsasya mudra, left hands in pataka,1 relaxed at the sides and bent at the elbow. This tableau from Padmini Chettur’s Varnam, performed during the 2016 Kochi-Muziris Biennale, encapsulates a broader transformation: the migration of contemporary Indian dance into infrastructures designed primarily for visual art.

This article theorizes that transformation through the lens of infrastructural intermediality, which I define as a form of institutional choreography – the ways in which economic systems, spatial architectures, and curatorial protocols condition relations of form, space, and labour in contemporary dance. Visual art institutions in India – from the Kochi-Muziris Biennale to private museums – do not merely host performance but actively choreograph its aesthetics, economies, and publics.

Two intertwined forces animate this institutional choreography: neoliberal economics and caste hierarchies. Since liberalization in the 1990s, the expansion of art infrastructures through private patronage, international funding, and market-driven logics has offered dancers new audiences and resources, even as these same structures reproduce inequalities of access, labour, and legitimacy. The migration of dance into visual art spaces thus raises pressing questions about how institutions choreograph the value and visibility of performance.

The discussion unfolds through historical and contemporary genealogies that trace the porous boundaries between visual and performing arts within Indian modernism, the ‘performative turn’ of the 1990s, and the rise of alternative art spaces that reconfigured both black box and white cube infrastructures. It situates the Kochi-Muziris Biennale as a paradigmatic case of institutional improvisation, where economic imperatives, spatial reconfigurations, and caste-class hierarchies choreograph the inclusion and visibility of dance. A focused case study of Padmini Chettur illustrates how re-skilling for exhibitionary contexts redefines choreography under these conditions. By foregrounding infrastructural intermediality, I aim to shift attention from individual artistic innovation to the broader systems of support, display, and labour that make contemporary dance possible – and precarious – in twenty-first-century India. In doing so, the article reframes performance not as a purely ephemeral art of the body, but as a socially embedded practice shaped by the infrastructures that sustain and constrain it.

The Long Performative Turn: Intersecting Genealogies of Visual and Dance Practices in India

The convergence of visual and performing arts in India is rooted in the interdisciplinary orientation of visual art modernism (roughly 1940s–1980s), a movement that persistently challenged and destabilized rigid boundaries between artistic media. Far from being a peripheral element, the performative was constitutive of modernist practice, offering artists a means to articulate anti-colonial, cosmopolitan, and transnational identities. As Geeta Kapur (2000), Partha Mitter (2007), and Sonal Khullar (2015) note, Indian visual art modernism rejected the Euro-American valorization of medium purity, embracing instead translation across painting, sculpture, film, photography, and performance. This intermedial ethos allowed artists to move beyond the colonial art school and the confines of nationalist aesthetics, situating modernism itself as a performative negotiation.

Individual practices underscore this orientation. M.F. Husain’s Through the Eyes of a Painter (1967), a film commissioned by the Films Division of India, staged painting in dialogue with rhythm and gesture, while Bhupen Khakhar, in works like Truth is Beauty and Beauty is God (1972), blurred painting, photography, and performance by orchestrating playful exhibition openings and embodying mythic and archetypal characters.2 Later artists such as Nikhil Chopra extended these tendencies into explicitly photographic performances, underscoring continuity rather than rupture between modernism and contemporary live art. Seen in this light, the migration of dance into visual art institutions emerges not as an anomaly but as part of a longer trajectory in which visual art modernism persistently looked towards performance as both form and method.

By the late 1980s and 1990s, amid declining state patronage and the rise of neoliberal reforms, Indian contemporary art – emerging in 1989 after the era of Indian modernism – underwent the ‘performative turn’, shifting away from modernist strategies of representation towards new modes of engaging art and politics (Allana, 2021).3 Artists critiqued the art object and gallery system, embraced collaboration, and turned to performance, informality, and ephemerality, privileging process, duration, and collective action over product and individual authorship, as seen in the social art projects of the SAHMAT Collective.4 This reorientation, which Kapur (2000) links to neoliberal internationalism’s delinking of growth from nationalism, gained urgency in the wake of political upheavals such as the 1992 destruction of the Babri Masjid, prompting artists like Rummana Hussain and Vivan Sundaram to mobilize the body as archive, testimony, and site of public engagement.5

New infrastructures reinforced this shift. Visual art collectives like KHOJ International Artists’ Association are purported to have nurtured experimental practices across the 1990s, exemplifying what I term infrastructural intermediality: the circulation of artistic labour across media within supportive institutional frameworks. Founded in 1997, KHOJ quickly became a key incubator for performance through residencies, workshops, and the ‘Khoj Live’ festival series – initiatives that the organization defines as ‘public performances’, ‘live action’, ‘real-time performance interventions’, and ‘pre-planned studio-based compositions’ (NDTV, 2016; Sood, 2015). Its regional networks – including Vasl in Pakistan, Britto in Bangladesh, Theertha in Sri Lanka, and Sutra in Nepal – helped consolidate performance art as a shared South Asian practice (Kumar, 2020).

Thus, performance art in India, while attentive to global precedents, emerged not as a critique of theatre but as an extension of visual art modernism’s intermedial focus. By the 2000s, endurance pieces, delegated performances, and live installations had become central to Indian performance art.6 Ephemerality, site-specificity, and duration were institutionalized as dominant aesthetic values, while visual art infrastructures – through their curatorial protocols, funding models, and exhibition frameworks – actively choreographed the very forms performance could take.7 In this way, the performative turn consolidated a new cultural ecology in which visual art institutions became critical sites for the production and circulation of embodied practices, setting the stage for contemporary dance’s entry into the exhibitionary sphere.

Contemporary Indian dance itself reveals deep entanglements with visual modernism.8 Uday Shankar’s India Cultural Centre in Almora (1930s–40s) cultivated an explicitly intermedial pedagogy, combining classical and folk performance with visual art, music, and theatre (Khullar, 2018). His collaborations with the Swiss artist Alice Boner – who sculpted and photographed his movements – underscored how sculptural form and dance mutually informed one another, aligning his practice with the ethos of Santiniketan’s Kala Bhavan, the art school founded in 1919 by Rabindranath Tagore and renowned for its interdisciplinary pedagogy integrating fine arts, craft, performance, and intellectual inquiry within a modernist yet distinctly Indian framework (Sarkar, 2021, 2022). Chandralekha, one of the most influential figures in late twentieth-century Indian dance, extended this orientation: during her hiatus from performance, she worked as a graphic designer and exhibition curator, and later collaborated with visual artists like Dashrath Patel, Anish Kapoor, and Hiroshi Teshigahara. Works such as Navagraha (1972), Raga (1998), and Sloka (1999) exemplify her integration of minimalist, sculptural, and graphic idioms into choreography (Bharucha, 1995).

Other choreographers deepened this dialogue. In Chrysalis (1989), Astad Deboo, in collaboration with the architect Ratan Lal Hiboi, transformed a confined box into a stage where isolated body parts, animated through vents, appeared as independent sculptural forms – revealing his acute choreographic attention to line, shape, and space. Navtej Johar’s Dravya Kaya (2010) foregrounded the materiality of epic objects, while Surjit Nongmeikapam’s Black Pot and Movement – Touching Manipur (2013) staged an encounter between pottery and dance. Jayachandran Palazhy’s City Maps (1999) and Maya Krishna Rao’s A Deep Fried Jam (2002) experimented with multimedia installations, and Anusha Lall’s Chaap (2007–08), co-created with the visual artist Giti Thadani, explored the spatial dimensions of bharatanatyam. Collectively, these works demonstrate how choreographers expanded their vocabularies through sustained engagements with visual forms.

By the 1990s and 2000s, these experiments increasingly entered exhibitionary and alternative spaces. Chandralekha’s performances at the Tramway Theatre in Glasgow (1992) and Queens Museum (1995) exemplified this shift, while Preethi Athreya’s Pillar to Post (2007) staged an embodied dialogue with Valsan Kolleri’s sculptures at Bodhi Space in Mumbai. These moves were not merely aesthetic gestures but can be understood as responses to infrastructural realities. Limited state support, a scarcity of dedicated venues, and bureaucratic inertia pushed choreographers towards galleries, repurposed heritage sites, and defunct industrial spaces. Filling the vacuum left by underfunded state museums that Geeta Kapur critiqued as disconnected from experimental practice (Ginwala, 2011), private museums and artist-led initiatives ‘re-skilled’ both the white cube and the black box as curatorial sites for contemporary choreography.9

This infrastructural improvisation manifests in diverse forms in the 21st century. Organizations like the Pickle Factory Dance Foundation in Kolkata transform warehouses and cinemas into performance sites, while black box theatres such as Odd Bird Theatre in Delhi, VYOMA Artspace & Studio Theatre in Bengaluru, and G5A in Mumbai emphasize flexibility and intimacy. At the same time, white cube spaces established by the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (Delhi), Experimenter Gallery (Kolkata), and Devi Art Foundation (Gurgaon) tether dance to transnational circuits of art and exhibition-making, reflecting the role of private collectors in energizing contemporary practices that exemplify multidisciplinary curatorial models. Together, these infrastructures expand the geography of performance, repositioning dance within broader global art economies.

Political contingencies significantly shaped the trajectory of contemporary Indian dance, compelling choreographers to reorient their practices towards non-traditional spaces. Mandeep Raikhy’s Queen Size (2016), conceived as a response to the criminalization of homosexuality under Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, deliberately circumvented the proscenium stage. Instead, the production toured seventeen Indian cities between 2016 and 2018, reaching more than four thousand spectators with 38 performances. Anticipating censorship and bureaucratic obstacles, Raikhy co-organized the tour with Sandbox Collective, mobilizing resources through crowdfunding to enable performances in alternative venues. These included intimate domestic sites, such as a dining room and kitchen in Imphal where audiences perched on counters around a gas stove, as well as cultural and activist spaces like Harkat Studios in Mumbai, the Conflictorium in Ahmedabad, SPACES in Chennai, and a law chamber in Guwahati. Such strategic choices demonstrate how choreographers negotiate precarity by creating counter-institutional frameworks that align aesthetic experimentation with political advocacy. According to Raikhy, Queen Size required non-traditional venues for two reasons: first, because its staging – a duet between two men performed on a charpoy (woven cot) – invited an intimate and reflexive spectatorship around sexuality, desire, and privacy; and second, because each performance was followed by workshops on gender and law that demanded settings conducive to dialogue and debate. In his view, these conversations could not have unfolded within mainstream state-funded institutions, where bureaucratic oversight, cultural conservatism, and political pressures often foreclose open engagement with questions of sexuality and dissent (Raikhy, email to author, 31 March 2017).

The black box/white cube distinction helps clarify what is at stake in these spatial reconfigurations. Long associated with experimental theatre and dance, the black box emphasizes immersive flexibility, while the white cube, with its colonial and neoliberal legacies of neutrality and timelessness, positions performance within circuits of art-world value.10 In India, both typologies were reshaped: reimagined mills, bungalows, and galleries facilitated choreographic innovation beyond the proscenium but also bound dance to uneven economies of visibility, prestige, urban regeneration, and cosmopolitan power. This double bind – spaces enabling experimentation even as they tether choreography to neoliberal regimes of value – is what I term infrastructural intermediality.11

So far, I have traced how modernist intermedial practices, the performative turn in visual art, and the reconfiguration of infrastructures together shaped the conditions for dance’s migration to exhibitionary spaces. These developments reveal how choreographers were not simply reacting to aesthetic impulses but also negotiating institutional, economic, and political frameworks that choreographed the possibilities of performance. This dynamic of infrastructural intermediality, as I will show in my case study of Padmini Chettur, is especially evident in the ways she strategically repositions her work in response to shifting and precarious institutional landscapes for contemporary dance in India.

Padmini Chettur’s Re-skilling to Dance Exhibition

Padmini Chettur’s trajectory reveals how contemporary Indian dance negotiates the economic and symbolic capital of visual arts infrastructures while maintaining a rigorous inquiry into the form and politics of movement itself. Trained in bharatanatyam yet committed to abstraction, she has cultivated a vocabulary of slowness, stillness, and geometrical precision that resists both devotional narrative and neoliberal spectacle.12 Over more than two decades, she has expanded choreography into installation and spatial experimentation through sustained cross-disciplinary collaborations with designers, architects, and sound artists. In her solo beautiful thing 2 (2011), for instance, the designer Zuleikha Chaudhari’s suspended light structure functioned as an architectural partner, reframing Chettur’s body as sculptural form and compelling spectators to move, crouch, and reposition themselves within the performance space. Works such as this blur the boundaries between performance and installation, making the museum not simply an alternative but a logical site for their presentation.

Chettur’s contemporary practice confronts a double marginalization: within India, where state-funded dance festivals prioritize either classical idioms or spectacular hybrids, and internationally, where her work risks being provincialized as ‘Indian contemporary dance’ within a Euro-American festival economy. These institutional frictions help expand her movement into the visual arts sphere. Museums and galleries – buoyed by private collectors, biennale funding, and global curatorial networks – have provided Chettur with alternative audiences, slower temporalities, and new economies of support: production fees, installation budgets, and exhibition programming that offset the shrinking opportunities of the international touring circuit. Chettur herself acknowledges that her turn to non-traditional venues was also motivated by financial sustainability.13

Several projects exemplify these dynamics. Wall Dancing (2012), performed in Chennai’s Focus Art Gallery and subsequently in multiple white cube venues, transformed the gallery into a three-hour environment of slow, sculptural configurations. Five dancers explored micro-relations between body and wall through deliberately slow configurations, inviting viewers to move freely, choose perspectives, and escape the ‘tyranny of viewing’ (Chettur, 2012). beautiful thing 1 (2009), originally created for the proscenium, is a choreographic exploration of time in which dancers construct and manipulate blocks of movement like segments of an equation, layering bodily precision with spoken text to produce a minimal yet resonant performance. Years later, the work circulated in a different form as part of the exhibition ‘Drawn from Practice’ (Experimenter Gallery, Kolkata, 2018), where it appeared as a two-channel video installation alongside choreographic notes and sketches. What emerged was not a simple restaging but a deconstruction of the piece by foregrounding the deep interrelation between planning, preparation, and presentation in Chettur’s practice. By foregrounding choreography as research and notation as a creative act, this low-cost, transportable format demonstrated how dance documentation could circulate in visual arts economies, providing visibility and viability without the logistical demands of live touring.14

Taken together, these works show how Chettur engages what Claire Bishop (2018) describes as the shift from the bounded temporality of the theatrical event to the extended temporality of exhibition, while insisting on slowness as a political form. Central to Chettur’s aesthetic is a radical deceleration of movement. In contrast to a dance economy that rewards speed and virtuosity – mirroring neoliberal imperatives of productivity – her choreography cultivates durational slowness and active stillness. As Helmut Ploebst (2009) observes, this ‘gift of slowness’ not only compels spectators to confront their own temporal habits but also reframes attention itself as a political and ethical practice. In this sense, Chettur’s work challenges both artistic and economic logics, situating dance as a mode of resistance to dominant structures of value and temporality.

Additionally, Chettur foregrounds infrastructural intermediality not as opportunism but as necessity: a negotiation with neoliberal art economies in which dance gains visibility only through re-skilling and reconfiguration. Re-situating choreography within the exhibitionary complex, she tests the limits of dance as both art and labour. Her practice suggests that the convergence of the black box and the white cube is less architectural than institutional, structured by the politics of funding, attention, and spectatorship.

Bishop’s concepts of re-skilling (2011) and dance exhibition (2018) sharpen this analysis. Re-skilling names the translation of disciplinary competencies across media – choreographers adapting works for museums, or visual artists employing performers to animate installations. Dance exhibition describes the hybrid apparatus produced by the convergence of stage and gallery, generating durational, looped, or re-performable formats that align with exhibitionary rather than proscenium logics. In India, this hybridization has been pronounced, given the simultaneous rise of black box theatres and private museums in the neoliberal era. Crucially, this apparatus does not simply house performance but reshapes its temporality, structure, and reception, while demanding new forms of labour from artists recalibrating to institutional protocols.

Chettur’s career thus provides a critical lens on the evolving relationship between contemporary Indian dance and global visual-arts infrastructures. By insisting on a ‘neutral body’ that resists spectacle while navigating the precarities of the performance economy, her work demonstrates how choreographic experimentation and institutional adaptation are inextricably entwined. Her dances are not merely site-specific but institutionally specific, responsive to the funding ecologies, curatorial discourses, and economies of attention that sustain them. My interest in this article concerns her specific situatedness within ecologies, discourses and economies of visual art infrastructures and how they reshape the aesthetics and reception of her work. In doing so, Chettur illuminates how infrastructural intermediality operates as both a mode of survival and a space of aesthetic invention for contemporary Indian dance.

The Kochi-Muziris Biennale as Choreographic Institution

The Kochi-Muziris Biennale (KMB) translates the intermedial approach of Indian visual art modernism and the performative turn into a city-scale cultural institution. Conceived in 2010 by the artists Bose Krishnamachari and Riyas Komu, KMB was a crucial artist-led curatorial initiative that sought to fill a deep infrastructural vacuum in India’s contemporary art landscape while maintaining conversations with the international art world.15 In contrast to Mumbai and Delhi – where commercial galleries and private collectors consolidated a white cube culture – Kochi lacked significant museal infrastructure. KMB was thus both intervention and improvisation: in the absence of permanent institutions, it turned the city itself into an exhibitionary space, repurposing heritage properties – abandoned warehouses, colonial bungalows, spice depots – into venues that redefined the relationship between art, site, and audience. In this sense, the Biennale not only filled a cultural void but also exemplifies what Kapur (2013) has called a ‘poor man’s museum.’

In a country with limited state investment in modern and contemporary art museums, KMB offered a recurring, temporary infrastructure in place of permanent collections. Supported by Kerala state funding, private collectors, nonprofit organizations, corporate sponsors, foreign embassies, and universities, the Biennale reoriented attention away from acquisition towards exhibition as process. Emerging in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis – when foundations slowed acquisitions and art markets contracted – KMB positioned itself as a vital alternative. It quickly became South Asia’s premier biennale, illustrating how infrastructural voids can catalyze experimental formats, including the integration of performance and dance.16

This turn towards experimentation was also visible in KMB’s curatorial structure. The Biennale’s curatorial model straddles two global templates. On one hand, it aligns with the Venetian format: each edition is curated by a prominent artist, mobilizes diverse funding streams, and fuels urban regeneration and tourism while attracting international capital. On the other, it resonates with Southern biennales such as Havana (1984) and Johannesburg (1990s), which relied on infrastructural improvisation and foregrounded Global South practices as counter-discourses to Euro-American dominance. This dual orientation – participating in, yet unsettling the global biennale economy – is central to KMB’s identity. In India, however, it is further inflected by neoliberal reforms of the 1990s and caste-based exclusions in cultural labour markets. Performance studies scholarship (Jackson 2011; Wilbur 2020) underscores how institutions shape choreographic possibilities by controlling temporalities, spatial arrangements, and access to resources; in India, these dynamics intersect with caste hierarchies to produce layered forms of visibility, legitimacy, and precarity.

The 2016 edition, curated by Sudarshan Shetty, marked a decisive turn to the temporal arts: nearly one-tenth of its 97 participants were performers (Khurana, 2016). Shetty positioned performance as a constitutive principle of the Biennale’s intellectual project, articulating his ‘core curatorial question’ as an inquiry into what tradition might mean ‘not as a stagnant or historical thought, but as an active concept integrated within contemporary reality’ (D’Souza and Manghani, 2017). To convey this sense of tradition as an active process, Shetty foregrounded performance as a medium that materially, philosophically, and politically engages with time, drawing inspiration from wide-ranging conversations with practitioners of theatre, poetry, film, music, and dance (News Editor, 2016). Works such as Padmini Chettur’s Varnam, Anamika Haksar and Zuleikha Chaudhari’s theatre projects, and endurance-based practices by artists like Mansi Bhatt exemplified this commitment.17 As Scroll magazine noted, the 2016 edition ‘will be remembered for its turn to the temporal arts,’ crystalizing Shetty’s conviction that performance could embody tradition as an active, contemporary process (Khurana, 2016).

Within this broader embrace of performance, Chettur’s Varnam emerged as a particularly charged intervention. Reimagining one of bharatanatyam’s most canonical forms, Mohamana Varnam (a central, extended piece of the bharatanatyam repertoire that combines pure dance and expressive storytelling), Chettur reframed the form as inquiry rather than preservation. She departed from traditional structures by replacing jatis (rhythmic sequences) and nritya (abstract movement) with an alternative physical vocabulary, incorporated contemporary women’s texts into the sahityam (expressive section) and treated the body as anatomical instrument rather than codified vessel. Performed on a low wooden dais, the piece evoked the traditional bharatanatyam recital stage while unsettling its associations through its placement in the Biennale’s exhibitionary space. In this context, Chettur’s reworking of the varnam was absorbed into the Biennale’s experimental programming, situating dance amid contemporary art practices and making it accessible to publics outside classical circuits. By situating the varnam in this plural, cross-disciplinary space, Chettur simultaneously critiqued the insularity of the bharatanatyam community and the ahistoricism of India’s contemporary dance movement, proposing instead a reconfigured encounter between tradition and contemporaneity. Staged as a three-hour durational loop in David Hall, Varnam allowed audiences to enter and exit at will – aligning both with the iterative temporality of the varnam and what performance scholars describe as the ‘exhibitionary mode’ of time: continuous, open-ended, and resistant to narrative closure.18 Yet infrastructural limits curtailed the live work: it was presented only during the opening week and thereafter replaced by video documentation, exposing the paradox of KMB’s embrace of liveness – celebrated as contemporaneity yet subordinated to circulation, tourist schedules, and financial constraints.

KMB’s choreographic operations unfold across economic, spatial, and temporal registers. Spatially, it reconfigures colonial architecture – verandahs, courtyards, spice warehouses – into art venues, compelling artists to negotiate uneven floors, open passageways, and improvised sightlines. Temporally, it shifts dance from event time to exhibition time, privileging looping sequences and durational presence over climactic arcs. Economically, the Biennale mobilizes state funding, private sponsorship, and tourist revenue, instrumentalizing performance for urban branding, tourism, and capital accumulation. Rather than functioning as a museum in the conventional sense, the Biennale becomes what Kapur (2013) has called a ‘poor man’s museum,’ offering performers a rare platform within visual art infrastructures. Its turn to performance illustrates how curatorial practice itself can operate choreographically – organizing time, bodies, and publics within exhibitionary architectures.

Yet these enabling operations are inseparable from their limits. The migration of dance into visual art institutions in India must also be understood within broader neoliberal cultural economies and entrenched caste hierarchies. While biennales and private museums provide choreographers with visibility, funding, and curatorial legitimacy otherwise absent in state infrastructures, but they also tether dance to market-driven logics and elite cultural consumption. KMB exemplifies how contemporary art institutions in India operate at the intersection of economic imperatives, spatial experimentation, and labour hierarchies – producing what can be understood as institutional choreography. This choreography, shaped by neoliberal capital, caste-class dynamics, and the repurposing of colonial heritage sites, not only enables but also implicitly governs the inclusion, form, and labour conditions of dance.

At the same time, KMB aligns closely with the global ‘Venetian biennale format,’ where art is mobilized as an instrument of modernization, urban regeneration, and tourism.19 In Kochi, billboards declaring ‘Invest in Biennale City’ and official branding of Kochi as a ‘Biennale City’ reveal how the festival is framed as an engine for cultural visibility and real estate development. This reliance on corporate and foreign sponsorship ensures that even ephemeral performance forms are assessed in terms of their ability to attract audiences, enhance city prestige, and generate capital.20 Dance – often described as ‘immaterial labour’ without a fixed end product – is thus instrumentalized for commercial gain, its presence choreographed by institutional priorities of spectacle, circulation, and prestige.

As Kapur (2013) notes, biennales generate provisional networks linking state and private finances, public spaces and elite enclaves, and artists across disciplines. Yet these networks are deeply entangled with economic interests, as Meiqin Wang (2008) also observed in post-1990s Asian biennales. In Kochi, this entanglement forces dance to navigate a tension between its processual, ephemeral nature and the demands of neoliberal accumulation, raising the critical question: where does dance exist as an autonomous art form within a commercially choreographed environment?

The Biennale’s institutional choreography extends further into the realm of labour, where inequities become stark. Budgetary constraints limited the duration of Chettur’s Varnam and restricted compensation for her ensemble. In an interview with Scroll Magazine, Chettur remarked on her surprise that, after being invited, ‘the space [at the Biennale] does not seem very prepared’ (Khurana, 2016). In our conversation (2018), she clarified that David Hall was not her preferred venue; Shetty insisted on its intimacy, while she had envisioned a larger frame for the work, underscoring the gap between curatorial intent and choreographic need.21 She also revealed that she had hoped to create a six-hour performance – aligning with the Biennale’s durational ethos – but Shetty persuaded her to reduce it to three hours for the opening week, citing budgetary constraints in paying her ensemble. The subsequent replacement of the live work with video epitomizes a structural irony: a Biennale invested in privileging temporal processes over material objects failed to prioritize the labouring bodies that made this intervention possible. This aligns with longstanding critiques from artists and scholars that museums disregard dancers’ health, safety, and labour.22 Chettur’s experience raises broader questions: do visual art institutions genuinely value the ephemeral labour of dance, or merely the vitality it brings to exhibitions? Is dance included as integral practice, or as spectacle serving neoliberal appetites for bodies and affect?23

These questions become sharper when viewed against the Biennale’s broader reliance on precarious labour. Delayed or absent payments to contractors, daily wage labourers, and fabricators at the Biennale, many of whom come from Dalit and working-class communities – underscore how infrastructural improvisation rests on the devaluation of marginalized labour.24 While choreographers and curators, largely from upper-caste backgrounds, enjoy visibility and symbolic capital, the indispensable contributions of maintenance workers, renovators, and stagehands remain unacknowledged. Bharatanatyam – one of the main sources for Chettur’s Varnam and a practice shaped by Brahminical ‘reform’ – continues to be valorized within elite circuits like the Biennale, while performance traditions rooted in Dalit and working-class communities struggle for recognition.25 By staging dance in repurposed colonial properties and emphasizing forms legible to elite audiences, the Biennale risks reinscribing historical exclusions. In this sense, institutional choreography arranges bodies unequally, distributing visibility and precarity along entrenched social lines. KMB thus demonstrates how neoliberal economics, spatial reconfigurations, and caste-class inequities collectively choreograph the presence of dance in contemporary art institutions.

This dynamic resonates with Brahma Prakash’s critique of contemporary dance in India. In his essay The Contingent of Contemporaneity: The ‘Failure’ of Contemporary Dance to Become ‘Political’ (2016), argues that much of contemporary dance in India falls short of its political potential because it often becomes inward-facing, aestheticized, and commodified – more about self-experience, spectacle, and sensory immersion than about transforming or challenging conditions of power. He claims that the boundary between performer and spectator is frequently dissolved into a passive experience rather than creating a site of dissent or agitation. In the neoliberal present, contemporary dance tends to serve elite consumption, where politics becomes theme rather than material practice, and the means of production, institutional contexts, or economic inequalities are rarely confronted.

Prakash’s point underscores the structural issues that also surface at KMB. He stresses that the ‘failure’ is not merely aesthetic but structural: contemporary dance frequently invokes politics symbolically (through themes of resistance or experimentation) without materially engaging with inequities of caste oppression, precarious labour, or uneven access to training, funding, and platforms. He further points out that the very patronage systems sustaining contemporary art in India – corporate sponsorships, elite cultural foundations, art collectives, and biennale circuits – are themselves deeply exclusionary. These infrastructures reproduce hierarchies of class and caste, granting visibility and resources primarily to artists already embedded within privileged networks. In doing so, they reinforce the very social and economic exclusions that contemporary dance might otherwise seek to critique. For dance to become truly political, Prakash suggests, it must attend to these material conditions – who dances, who is seen, who is funded, and who is erased – rather than relying on abstract gestures of critique.

KMB crystallizes these tensions. While it provides choreographers with visibility, experimentation, and cross-disciplinary publics, it also reinscribes exclusions, demonstrating how neoliberal economics, caste-class inequities, and repurposed colonial spaces collectively choreograph the presence of dance in India’s contemporary art landscape. Recognizing these asymmetries is essential if we are to imagine infrastructures that not only sustain artistic innovation but also dismantle the exclusions embedded within India’s cultural economy.

Conclusion: Towards a Critical Understanding of Infrastructural Intermediality

The migration of contemporary dance into visual art institutions in India is not incidental but the result of long genealogies of intermedial experimentation, infrastructural improvisation, and institutional adaptation. From Indian modernism’s interdisciplinarity to the performative turn of the 1990s and the rise of biennales and private museums, choreographers have found new publics, resources, and aesthetic possibilities by entering exhibitionary frameworks. Yet these infrastructures also choreograph dance – dictating its forms, temporalities, and labour conditions – through the logics of site-specificity, spectatorship, and neoliberal cultural economies.

This dynamic, which I theorize as infrastructural intermediality, highlights the double-edged nature of institutional convergence. While visual art spaces create opportunities for experimentation and circulation, they simultaneously reproduce entrenched exclusions: privileging elite audiences, binding dance to urban branding, and obscuring the manual and technical labour – often performed by marginalized communities – that sustains these institutions. Caste and class hierarchies remain inscribed within the very architectures and economies that host contemporary performance.

To conceptualize infrastructures as forms of institutional choreography is to recognize that they do not merely house dance but actively shape its conditions of production, dissemination, and reception. The challenge, then, is not to reject infrastructural intermediality but to reimagine it: to cultivate infrastructures that sustain artistic innovation while dismantling inequities of labour and access. Only by doing so can contemporary Indian dance realize its critical and transformative potential within and beyond the exhibitionary frame.

Wzór cytowania / How to cite:

Singh, Arushi, Infrastructural Intermediality as Institutional Choreography: Contemporary Dance and Visual Art Institutions in India, „Didaskalia. Gazeta Teatralna” 2025, nr 189, DOI: 10.34762/cbyq-jz22.